Podcast Becoming FDR: The Personal Crisis That Made a President

In 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was sworn in for the first of his four terms as president of the United States....

Main Content

Lyndon Johnson and the 1965 Voting Rights Act

How Long? 9 minutes

After the 1964 electoral landslide, President Lyndon Johnson’s political position changed considerably. With a larger liberal majority in both houses of Congress secured, Johnson believed he now had an electoral mandate to move forward on the issue of civil rights. He wasted no time in setting a marker for his goals. In his 1965 inaugural address, Johnson intimated that he would pursue a more aggressive approach concerning a variety of social issues. Such rapid change would require moral fortitude:

If we fail now, we shall have forgotten in abundance what we learned in hardship: that democracy rests on faith, that freedom asks more than it gives, and that the judgment of God is harshest on those who are most favored.1

Johnson also stated in the speech that any attempt to deny justice to fellow citizens based upon the color of their skin constituted a betrayal of America and its ideals.2

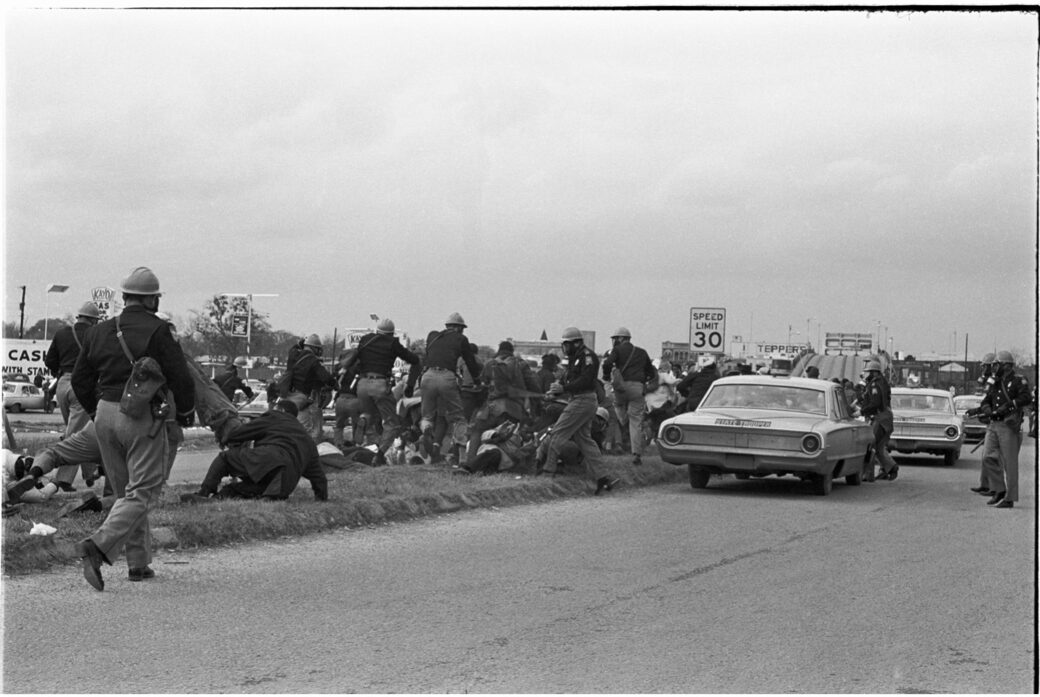

Less than two months later, on March 7, 1965, protestors led by civil rights leaders John Lewis and Rev. Hosea Williams were attacked by state police, local law enforcement, and an organized posse as they tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. This violent episode would come to be known as “Bloody Sunday.” Despite the success of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, many state and local governments refused to comply with federal law. As a result, civil rights leaders and activists continued to protest voter inequality and suppression and were drawn to Selma because only two percent of the city’s Black population had successfully been able to register to vote.3

An Alabama state trooper beats John Lewis as other marchers run toward the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

© 1965 Spider MartinPublic reaction was swift, due in large part to the abundance of images that documented “Bloody Sunday.” Television cameras had captured the assault and by that evening, Americans witnessed the violence as they watched the evening news.4 On March 9, 1965, President Johnson issued a statement in which he promised that experts were drafting federal legislation to protect voting rights. Once he had reviewed the draft and provided his input, he vowed to deliver the proposed legislation to Congress as a “special message.”5

On March 11, 1965, civil right demonstrators engaged in a sit-in at the White House. After arriving at the White House through the visitor entrance during public tour hours, the twelve protestors sat down on the Ground Floor, near the Library and Vermeil Room. Public tours were terminated during the protest as a precautionary measure. In the afternoon, the demonstrators moved to the East Garden Room. After several hours, President Johnson instructed the Secret Service to remove the individuals from the White House. However, demonstrations continued outside in Lafayette Park to draw attention to the violence in Alabama.6

After the violence in Selma, twelve protestors occupy the East Garden Room of the White House on March 11, 1965.

Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum/NARAOn March 13, President Johnson met with the Governor George Wallace of Alabama in the Oval Office. Others in attendance included Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach, special assistant and speechwriter Richard Goodwin, and White House special advisor Jack Valenti. Wallace asked Johnson to end the demonstrations in Alabama; Johnson responded by showing him photographs documenting police brutality. During the conversation, Johnson tried to appeal to Wallace’s sense of history, arguing that his legacy was more important than any immediate political advantage he might gain by opposing voting rights for Black Americans. Wallace agreed to allow another demonstration in Alabama and protect the protestors. He exited the White House and did not join Johnson in a press conference afterwards.7 Later, in his memoirs, Johnson concluded that the meeting with Wallace at the White House “proved to be the critical turning point in the voting rights struggle.”8 Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach called the meeting “the most amazing conversation I’ve ever been present at.”9

President Johnson believed that Selma provided an excellent opportunity for passage of a voting rights bill with provisions that would not be diminished by extensive compromise in Congress. He met with congressional leaders on March 14 in the Cabinet Room of the West Wing and decided that a joint address to Congress was necessary to show his support of the proposed legislation.10

Valenti directed Goodwin to draft Johnson’s speech before Congress. Goodwin had about eight hours to write a complete draft for the president. In fact, the speech was finished so late in the evening, Johnson delivered it from a typewritten copy rather than a teleprompter.11 It is often viewed as Johnson’s “greatest oratorical triumph.”12 The formal title of the address was “The American Promise” but it came to be known as the “We Shall Overcome” speech. Johnson instructed Goodwin that in the text of the speech, he “wanted to use every ounce of moral persuasion the Presidency held.”13

Alabama Governor George Wallace meets with President Lyndon Johnson at the White House.

Alabama Department of Archives and HistoryGiven on March 15 in the chamber of the House of Representatives, over 70 million Americans watched on television.14 President Johnson made it clear that he was addressing all Americans in the speech, not only southerners or African Americans:

There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is no Northern problem. There is only an American problem.15

The issue at hand was voting rights, yet Johnson made it clear it was the most intrinsic principle of the American promise that motivated his words and justified action:

Our mission is at once the oldest and the most basic of this country: to right wrong, to do justice, to serve man.16

The problem of voting rights was not something the African-American community should bear alone. Instead, all citizens needed to consider it as their cause:

What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and State of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.17

Johnson grounded his arguments about voting rights within a broader moral context. While the immediate issue was ensuring voting rights for all Americans, the larger purpose was fulfilling America’s moral mission. The broadening of the scope enabled Johnson to move past the imminent crisis of Selma to a grander, more inclusive vision that emphasized unity rather than division.18

Finally, the inclusion of the line “we shall overcome” bolstered Johnson’s status within the Civil Rights Movement. The line came Pete Seeger’s civil rights folk anthem. Seeger stated he first heard the line sung by striking African American tobacco workers in the 1940s. Some believed that Johnson had co-opted the phrase for his own political purposes, but civil rights activist John Lewis, who watched the speech with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., remarked that King wiped away a tear when Johnson uttered the famous phrase.19

Watch an excerpt of President Lyndon B. Johnson's special message to Congress.

Credit: Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum/NARA

The speech was met with praise and accolades. Within twenty-four hours, the White House reportedly received 1,436 telegrams in support of Johnson’s stance, with only 82 telegrams against. Furthermore, a public opinion poll taken immediately after the address recorded that 76 percent of Americans were in favor of the proposed Voting Rights Act (VRA), with 16 percent against.20 Despite these early signals of support, Governor Wallace refused to mobilize the state National Guard to protect demonstrators in Alabama. Left without a viable option, President Johnson signed an executive order to mobilize and federalize the National Guard to provide such enforcement.21

Unfortunately, the violence did not stop. On March 25, 1965, Mrs. Viola Liuzzo, a white woman driving protestors between Selma and Montgomery, was shot and killed. The next day at 12:40 pm, President Johnson appeared in the East Room of the White House to give a televised address about the murder. The FBI had already arrested four suspects who were also members of the Ku Klux Klan. Joined by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, Johnson denounced the Klan and announced he would seek legislation to bring its activities “under effective control of the law.”22

Johnson, who had served in the House and the Senate before becoming Vice President and President, lobbied Congress hard to support the proposed Voting Rights Act. It passed the Senate on May 25, 1965, easily securing cloture with a 77 to 19 bipartisan vote.23 The legislation then moved to the House of Representatives, which passed it on July 9, 1965 with a vote of 333 to 85. On August 6, 1965, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law at the United States Capitol, with civil rights leaders and congressional proponents alongside him.24

President Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act at the United States Capitol on August 6, 1965.

Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum/NARAThe VRA made racial discrimination in local, state, and federal elections illegal. It also banned poll taxes and literacy tests. Lastly, it mandated oversight of nine southern states, which had historically prevented African Americans from exercising the right to vote. According to a longitudinal analysis of southern voting rolls, registration amongst African Americans increased dramatically in the region. Much of the impact was immediate. For example, Alabama increased its Black voter registration from 23.0% in 1964 to 56.7% in 1968; Louisiana increased from 32.0% to 59.3%; and Mississippi increased from 6.7% in 1964 to 59.4% in 1968. Also, the number of elected Black leaders in the region increased significantly.25

Johnson understood the historical significance of the 1965 Voting Rights Act and considered it the most important accomplishment of his presidency. In a recorded telephone conversation on January 15, 1965 with Dr. King, Johnson explained how critical it was to pass voting rights legislation:

And if we do that, we’ll break through—it’ll be the greatest breakthrough of anything, not even excepting the ’64 Act. I think the greatest achievement of my Administration. I think the greatest achievement in foreign policy, I said to a group yesterday, was the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. But I think this’ll be bigger. Because it’ll do things that even the ‘64 Act couldn’t do.26

In 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was sworn in for the first of his four terms as president of the United States....

Mark K. Updegrove shares new historical perspectives on the Kennedy presidency from his recent book, Incomparable Grace: JFK in the...

Native Americans hold a significant place in White House history. For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples, including the Nacotchtank and...

Every year since 1981, the White House Historical Association has had the privilege of designing the Official White House Christmas Ornament....

In 1821-1822, Susan Decatur requested the construction of a service wing. The first floor featured a large kitchen, dining room,...

For more than a century, thousands of Americans have gathered in Lafayette Park across from the White House to exercise...

In 1816, Commodore Stephen Decatur, Jr. and his wife Susan moved to the nascent capital city of Washington, D.C. With...

Long before the emergence of the United States and Italy as modern nation states were influenced by classical writers, philosophers,...

The collection of fine art at the White House has evolved and grown over time. The collection began with mostly...

On November 22, 1963, about two hours after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson took the...

For more than two centuries, the White House has been the home of American presidents. A powerful symbol of the...

The young national capital at Washington, D.C. became the center of the War of 1812 with Great Britain during the...