Collection The Johnson White House 1963 - 1969

On November 22, 1963, about two hours after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson took the...

Main Content

The Capitol Connection

How Long? 11 minutes

It is probably safe to say that the presidential inauguration is the transcendent public ritual of American representative government. Unlike the coronation of a monarch or any ritual associated with the rise to power of a dictator or autocrat, the inauguration of a president is a cyclical, regularly scheduled event held every four years, and one to which, perhaps thankfully, since the ratification of the 22nd Amendment in 1951 no one individual can be subjected more than twice. It is also a ritual that involves all three branches of the federal government at the seat of the first branch—the legislative—at the U.S. Capitol.

The regularity of presidential inaugurations lends a reassuring sense of stability, continuity, and permanence to a political system that permits turnover in officeholders and change in policy agendas. Moreover, it is a peaceful change in government, unlike the violence that so often accompanies a new head of state elsewhere. Lastly, the evolution of inaugural ceremonies, from the relatively simple affair of George Washington’s first inaugural to the current lavish, expensive, and choreographed event calculated to maximize media exposure, mirrors similar changes in American political culture in which money, the media, and appearance rather than reality prevail.

Consider the symbolism of inauguration day. In instances in which a new president has been elected, the outgoing president and a delegation of congressional leaders escort the president-elect from the White House to the Capitol.1 Members of the Joint Congressional Inaugural Committee escort the president-elect from a holding room in the Capitol outside to the inaugural platform on the West Front. The chief justice of the Supreme Court administers the oath in the presence of the public—the electorate who chose the president—as members of Congress, past and present, justices of the Supreme Court, members of the diplomatic corps, and other dignitaries bear witness. In this way, all three branches of the federal government and the public they serve join in a ritual of renewal and reaffirmation.

On March 4, 1917, crowds gathered to observe the second inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson on the East Front of the US Capitol, where 27 presidents have taken the oath of office. In 1981 the event was moved to the West Front.

Library of CongressThe administration of the oath of office as a ritual of reaffirmation combines the worlds of the sacred and the profane—or in other terms—religion and politics. The president-elect with hand on an open Bible takes the oath as specified in Article II, section 1, of the Constitution: “I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

In promising to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution, the secular Bible of our form of government, the ritual invokes the solemnity of sacrament. Elements of the sacred and the profane coalesce in a civic religion whose sacred texts are the Bible and the Constitution, though not necessarily in that order.

Just as feasts and celebrations follow other sacred ceremonies, the remainder of inauguration day takes the form of festival. The president and privileged members of Congress have lunch in the Capitol’s Statuary Hall, where dead American heroes in marble and bronze link past with present. In hosting the president, congressional leaders symbolically offer both the olive branch of cooperation and the none-too-subtle claim of priority of the first branch of government. The president and his entourage then travel back to the White House at the head of an increasingly elaborate parade. From a reviewing stand, the president watches as everything from baton-twirling high school bands to military marching units pass in review, acknowledging and celebrating the new occupant of the White House. The day concludes with inaugural balls that evening at various locations around the city, at which the political power elite parties with its corporate backers and major financial supporters.

President Harry S. Truman and his successor Dwight D. Eisenhower smile and wave as their car leaves the White House en route to the Capitol on inauguration day, January 20, 1953.

Library of CongressThe function of festival in this case seems to be to bring the consecrated one back down to the grubby secular world of social and political obligations— although most new presidents do not return to earth until they encounter their first foreign policy crisis or their first real opposition from Congress.

A brief historical survey of the Capitol component of presidential inaugurations reveals that although the ceremony has become increasingly stage-managed, the essential elements of sacred ritual and festival have always been present. Prior to 1937, when the date was changed to January 20 as a result of the 20th Amendment, inauguration day was set on March 4. The first inauguration, however, did not take place on March 4, 1789, but nearly two months later, on April 30, because Congress lacked a quorum necessary to do business, including counting the electoral votes cast for president and vice president.

The Constitution does not specify that president must go to Congress to take the oath of office, but Washington did so on April 30, 1789. Washington had been commissioned to command the Continental Army by the Continental Congress, and he had voluntarily resigned his commission at the end of the war in a show of military subordination to civil authority, so it came as little surprise that he swore the oath on the balcony outside the second-floor Senate Chamber of Federal Hall, the then-capitol in New York City. Because no Supreme Court justices had yet been appointed, Robert R. Livingston, chancellor of the state of New York, administered the oath. A Bible had to be borrowed from nearby St. John’s Masonic Lodge when none could be found in Federal Hall. Livingston raised the Bible; Washington bent over and kissed it, setting a precedent followed by most of his successors. The president then went back into the building and delivered his inaugural address in the Senate Chamber in the presence of both Houses of Congress.

Livingston raised the Bible; Washington bent over and kissed it, setting a precedent followed by most of his successors.

Following the inaugural address, the president and members of Congress walked to St. Paul’s Chapel for special services and prayers for the new nation—a further indication that although the Founding Fathers might have opposed government support for any particular religious establishment, they expected religion to support the state. A giant fireworks display that evening concluded inaugural observances.2

The first inauguration to take place at the Capitol in Washington, D.C., was one of the most significant in the nation’s history. Thomas Jefferson’s March 4, 1801, inauguration was the first instance in which the presidency changed political parties. It also was the result of the first time an election had to be decided by the House of Representatives. The House decided the election in Jefferson’s favor over his erstwhile running mate Aaron Burr only two weeks before inauguration day. Only one wing of the Capitol, the old Senate wing, had been completed, and the swearing-in ceremony was scheduled for the Senate Chamber. Jefferson walked the short distance from his lodgings at Conrad and McMunn’s boardinghouse on New Jersey Avenue, escorted by several members of Congress and a crowd of onlookers.3 The semicircular Senate chamber was crowded with an estimated 1,000 spectators, an impossible number given the size of the chamber, to hear Jefferson’s inaugural address, carefully worded to reassure the public and his Federalist opponents that continuity would prevail over change.4

The inauguration of Jefferson’s successor, James Madison, moved to the larger House Chamber in 1809, which continued to be the site until 1829, with the exception of James Monroe’s inaugural in 1817, which had to be held in front of the temporary Old Brick Capitol because the restoration of the Capitol had not been completed following the fire set by British troops in 1814.5

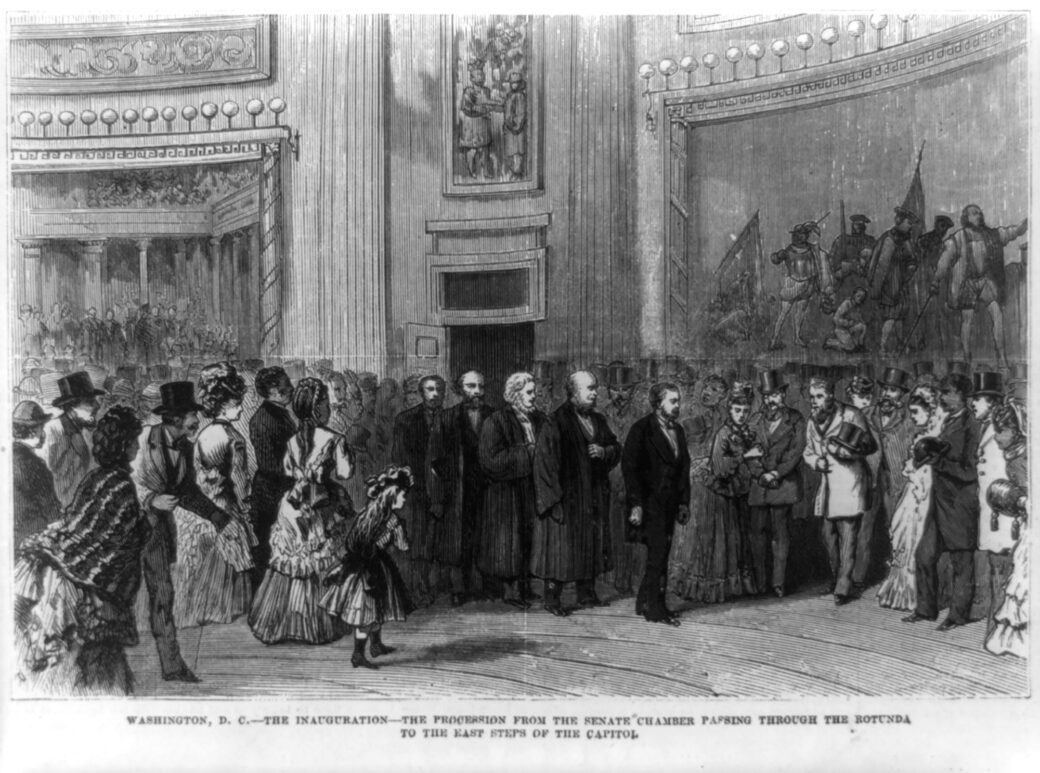

On March 4, 1873, President Ulysses S. Grant made his way through the Capitol to deliver his inaugural address on the East Steps. This wood engraving shows him moving with a procession from the Senate Chamber through the Rotunda in a traditional ritual of inauguration day.

Library of CongressIn 1829, however, the inauguration of Andrew Jackson as the seventh president of the United States moved the ceremony outside to the East Portico of the Capitol. A ship’s cable stretched across the central East Front stairs kept the large crowd back. At the close of the ceremony, the crowd pressed forward to greet Jackson, the cable broke, and the president had to flee on horseback. Spontaneously, the crowd followed down Pennsylvania Avenue in an improvised and chaotic parade.6 The ensuing reception at which an estimated 20,000 revelers trashed the White House has become notorious in American history.7

The East Front remained the usual site for presidential inaugurations until 1981. The Capitol was still a work in progress at the beginning of the Civil War in 1861 when Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office. The two new wings designed by architect Thomas U. Walter and constructed by army engineer Montgomery C. Meigs had been completed and occupied, but the cast-iron dome was still under construction.8 Its completion, Lincoln is reported to have said later, was a sign that the Union would survive the Civil War.9

Lincoln’s second inaugural came just as the Civil War was drawing to a close in 1865. A war-weary president ennobled the occasion with his inaugural address, which many consider the greatest speech in American history.10

Some scholars believe Lincoln's assassin John Wilkes Booth and other conspirators can be seen in this photograph taken by Alexander Gardner.

Library of CongressMost inaugural addresses are eminently forgettable— either droning generalities or blowsy platitudes. In recent memory, inaugural addresses have been, predictably, expressions of optimism as presidents exercise their role as the nation's chief therapist. John Kennedy’s inaugural speech may have set the tone, although more eloquently than his successors. Kennedy, the last president to wear the traditional stovepipe hat on inaugural day, also was the first president to use a poet, Robert Frost in Kennedy’s case, on the program.11

The apparent need for optimism even goes so far that each inauguration now must have an upbeat official theme, all variations on the innocuous, such as Richard Nixon’s “Forward Together” in 1969 and George W. Bush’s 2001 “Celebrating America’s Spirit Together,” both of which at least had the virtue of brevity over Bill Clinton’s 1997 “An American Journey: Building a Bridge to the 21st Century.”

Lincoln, however, did not see himself as a Dr. Feel Good therapist bearing tidings of rosy optimism, nor did he need to seek the services of a poet. His second inaugural address was a somber, deeply felt, and articulate meditation on the meaning of the Civil War to the soul of America. The last paragraph— “with malice toward none”—is rightly considered the most famous passage of any presidential inaugural speech.12

In keeping with tradition, the outgoing president escorts the president-elect to the U.S. Capitol for the inauguration. In 1929, President Calvin Coolidge poses with his successor President Herbert Hoover.

Library of CongressIncluding Jackson and Lincoln, 27 presidents took the oath of office at the East Front of the Capitol. Exceptions included vice presidents who succeeded presidents who died in office or resigned—John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Andrew Johnson, Chester A. Arthur, and Gerald R. Ford.13 William Howard Taft was sworn in on March 4, 1909, in the Senate Chamber because of bad weather and the advanced age of Chief Justice Melville W. Fuller. On January 20, 1945, Franklin D. Roosevelt overrode congressional protests and held his fourth inauguration at the White House; because of the war he felt an elaborate celebration was not called for, although some suggest that he was feuding with congressional leaders.14

In 1981, planners moved the inauguration of Ronald Reagan to the West Front of the Capitol, setting a precedent that continues to this day. The West Front location provides more space for spectators and a larger platform for dignitaries; but most of all, with its sweeping vista of the Mall, the West Front is best suited for televising the event and provides the new president his first opportunity to demonstrate that most important of qualities, being “presidential.”15

Reagan’s second inauguration in 1985 was unusual for a different reason. Because of bad weather, the ceremony moved inside to the Capitol Rotunda, the first time that location had been used for this purpose. It also was held on January 21 rather than the 20th, which fell on a Sunday. Reagan took the oath privately at the White House on Sunday and then publicly at the Capitol on Monday.16

In 1981, the inauguration of President Ronald Reagan was moved from the East Front to the West Front of the Capitol, setting a precedent continued by Presidents William J. Clinton (1993 and 1997), George W. Bush (2001 and 2005), and Barack Obama (2009 and 2013). The West Front allows a view from the Mall and provides more space for onlookers.

White House Historical AssociationGeorge W. Bush’s inauguration, on January 20, 2001, was the 68th time the oath of office was administered, the 54th time a president was inaugurated following his election, the 51st inauguration ceremony held in Washington, the 49th held at the U.S. Capitol, and the fifth at its West Front.

Although it is tempting to dismiss the pomp and pageantry of presidential inaugural ceremonies as just another indication of the triumph of style over substance in American political culture, in the case of the Capitol’s connection to presidential inaugurations, style is substance at least on this one occasion, when all three branches symbolically join in a national affirmation of purposeful unity.

On November 22, 1963, about two hours after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson took the...

In April 1789, George Washington took the oath of office in New York City. Constitutional guidelines for inaugurations are sparse, offering...

Americans are familiar with the ceremonies of Inauguration Day, when a new President takes the oath of office at the...

Elaine Rice Bachmann

NUMBERS 1 THROUGH 6 (COLLECTION I) WHITE HOUSE HISTORY • NUMBER 1 1 — Foreword by Melvin M. Payne 5 — President Kennedy’s Rose Garden by Rachel Lambert...

Read Digital EditionForeword, William SealeTaking the Oath of Office: The Capitol Connection, Donald R. Kennon"Not a Ragged Mob": The...

Benjamin Henry Latrobe's 1803 drawing of the State Floor indicates that the Red Room served as "the President's Antechamber" for the...

At 2:30 on the morning of August 3, 1923, while visiting in Vermont, Calvin Coolidge received word that Warren G. Harding was dead...