Collection Weddings and the White House

From First Lady Dolley Madison's sister Lucy Payne Washington's wedding in 1812 to the nuptials of President Joseph Biden and First...

Main Content

How Long? 5 minutes

The United States remained neutral during the early years of World War I, from the outbreak of hostilities in August, 1914, to April, 1917. As a result, the country continued to interact with both the Central Powers and Allied Powers.1 However, security for the White House, President Woodrow Wilson and those closest to him was becoming a concern on the eve of the entry of the United States in the war; and after Congress declared war it also authorized permanent protection of the president’s immediate family.2 There had already been at least one major instance of sabotage by German agents in the United States—the so-called Black Tom Explosion in Jersey City on July 30, 1916—and after April 1917 many Americans were concerned that German infiltrators would target the White House, members of the government and their families, and even civilians.

As anti-German sentiment spread quickly across America in the spring of 1917 even before the actual declaration of war, the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Investigation (later the Federal Bureau of Investigation), did not have enough manpower to monitor security in the nation’s capital and across the country.3 A Chicago businessman, Albert M. Briggs, pitched an idea to the Department of Justice to assist in investigating potential German agents by designing a volunteer force to “enforce patriotism and stifle dissent.”4 President Wilson approved the establishment of the American Protective League (APL) at a cabinet meeting on March 30, 1917.5 Sponsored by Briggs and additional Chicago volunteers, the APL was a privately funded organization established in Chicago at the People’s Gas Building and was eventually headquartered in Washington, D.C.6

While the Department of Justice approved of the investigative efforts of the APL, members of the force were not authorized by the federal government to carry weapons or make arrests. However, local police departments also lacked manpower, and so tacitly encouraged the APL to identify and even arrest suspicious individuals.7 By the fall of 1917, the League had enlisted an estimated 250,000 to 300,000 members in over 600 cities in the United States, including major cities like Chicago, New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C.8

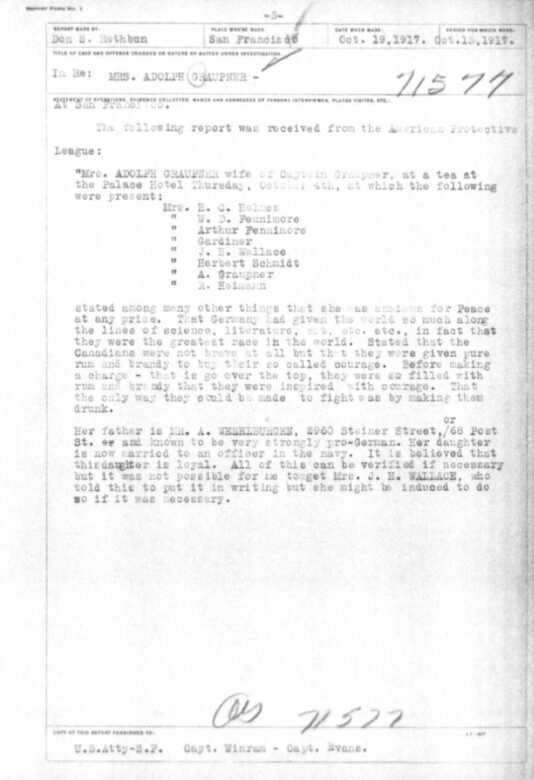

Scan of American Protective League report to Bureau of Investigation.

National Archives and Records AdministrationThe APL was created in part to respond to laws supported by President Wilson, such as the Espionage Act of 1917, and its stated purpose was to “stamp out perceived threats to the security of a nation at war.”9 Under the protection of these acts, Leaguers investigated anyone they deemed a threat to the United States, including Americans who disagreed with current policies. The APL did not work in conjunction with the Secret Service, but assisted the president in investigating potential subversive agents.

Due to both the fast-paced creation of the APL and secretive nature of its work that aligned with the Bureau of Investigation and the Secret Service, there was often confusion among officials over aspects of organizational authority. Secret Service members were tasked with protecting the president, the first family, the White House, and occasionally staffing undermanned bureaus in Washington.10 The creation of the APL meant the Secret Service no longer needed to fight the “home front war” on its own.11 In addition, the APL was often referred to by newspapers, such as the Washington Post, as a “secret service organization.”12

Government departments frequently confused Attorney General Thomas Watt Gregory in the initial weeks of the APL with officials in the Secret Service. However, his close relationship with President Wilson provided opportunities for Gregory to argue for the importance of domestic surveillance through the APL. Leaguers had the ability to purchase badges similar to those of the Secret Service.13 After many discussions among President Wilson, Treasury Secretary William McAdoo and Gregory, the Secret Service stepped back and allowed the APL to continue their duty of “taking action against disloyal socialists and pacifists by engaging in domestic surveillance and raiding businesses.”14

Letter from APL on their investigations of citizens regarding food hoarding.

National Archives and Records AdministrationThe most well-known action of the APL was in September 1918 when the Leaguers participated in a “slacker raid” in New York City, questioning more than 75,000 suspected draft dodgers.15 Due to the passage of the Selective Service Act in 1917 by Congress, the APL was able to assist in arresting between 20,000-25,000 draft dodgers and bringing them up for induction into the United States Army.16 The Leaguers attempted to bring safety to the American public, but they frequently overstepped their authority by making unwarranted arrests.

In 1918 President Wilson told Gregory that he was afraid giving the volunteers so much power could be dangerous.17 Nevertheless, the APL continued its work. Some believed that the safety of the nation was tied directly to the APL. The Washington Post reported in November 1918, “Even the signing of an armistice [on November 11] does not mean that the bars can be let down to the enemies of America.”18 Leaguers kept watch on hotels, restaurants, railroad stations, industrial plants, telegraph and telephone lines, steel mills, and the chemical trade.19 United States officials, including Gregory, proclaimed how the APL contributed to the safety of American citizens; saying that, “It is safe to say that never in its history has the nation been so thoroughly policed as at the present time.”20

The APL ended its operations by request of Attorney General Gregory in February 1919, three months after the war had ended.21 The Leaguers’ efforts during World War I extended from the Department of Justice to involvement with the Secret Service, which kept foreign agents at bay and secured America from spies within its own borders. The home front during World War I was defined partially by fears of German sabotage or influence within the American government. The increased security at the White House was part of a larger initiative across the country, where the Secret Service, Bureau of Investigation, and the American Protective League worked in tandem to keep America safe.

From First Lady Dolley Madison's sister Lucy Payne Washington's wedding in 1812 to the nuptials of President Joseph Biden and First...

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr., the nation’s only unelected president and vice president, served thirteen terms in Congress before rising to...

On January 20, 1969, Richard Nixon was inaugurated as the thirty-seventh president of the United States. During his time in the White...

Native Americans hold a significant place in White House history. For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples, including the Nacotchtank and...

Biographies & Portraits

Biographies & Portraits

What was it like to grow up in a home where some of the most important political decisions are being...

The collection of fine art at the White House has evolved and grown over time. The collection began with mostly...

On November 22, 1963, about two hours after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson took the...

Dwight D. Eisenhower was the only army general elected president in the twentieth century. His achievements were many — he was an...

President Harry S. Truman was close to his friends and associates, had a grin for strangers, but could be less...

The White House Historical Association and the Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project present this collaboration in an effort to open a...