Collection Presidential Inaugurations

In April 1789, George Washington took the oath of office in New York City. Constitutional guidelines for inaugurations are sparse, offering...

Main Content

How Long? 22 minutes

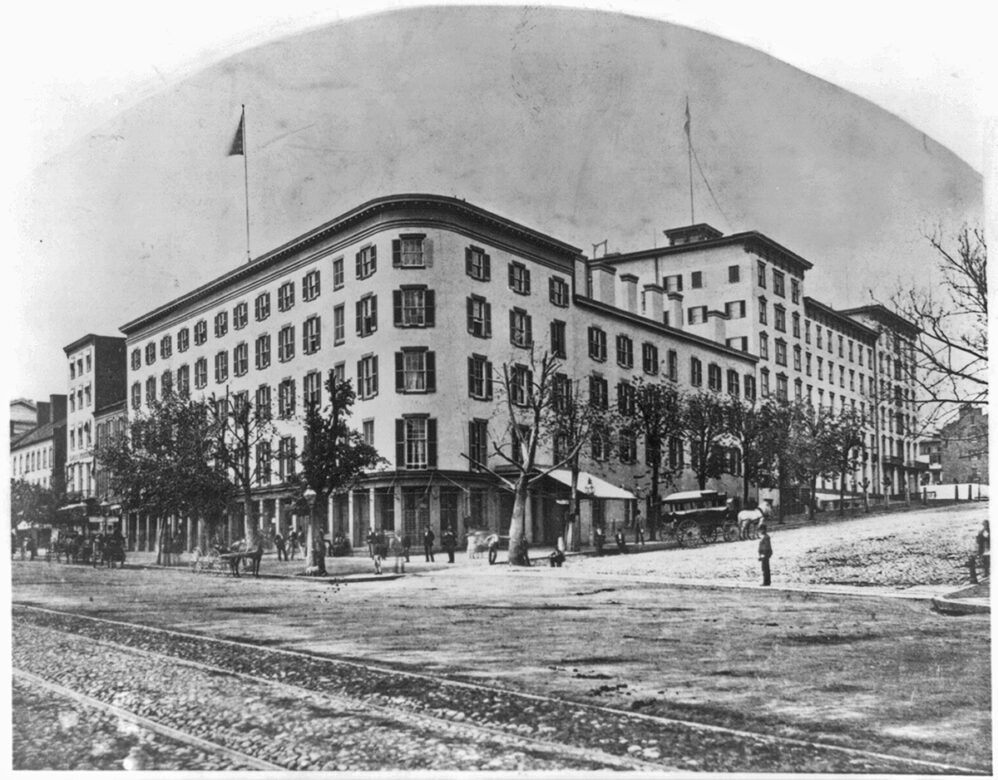

Willard’s, seen here during the Civil War, was comprised of five stories of well furnished rooms with elegant public spaces on the street level.

Library of CongressDuring the Civil War, the fighting at times came so close to the capital that the Lincolns could hear the sounds of battle from their country retreat at the Soldiers’ Home, 3 miles north of the White House.1 One of the officers in the Union Army charged with defending the capital noted in his tiny leather-bound diary:

"July 17, 1862: This night I slept in a chicken coop—rained hard all night.

August 30, 1862: Slept this night under an oak tree, on the ground, hungry and tired.

September 2, 1862: Slept on the ground, a hard night, and no mistake."2

Surely such discomfort was not unusual for the soldiers fighting a brutal four-year war that raged from Maryland to the Mississippi. But what is extraordinary is that the man doing the griping was Joseph Clapp Willard, proprietor with his younger brother, Henry Augustus Willard, of what was Washington’s grand hotel, the Willard. Thoughts of the comfortable beds and sumptuous meals that had made Willard’s a mecca must have gone through his mind. William Howard Russell, the famous British war correspondent, in town to cover the war, observed that one guest put away for breakfast: “black tea and toast, scrambled eggs, fresh spring shad, wild pigeon, pig’s feet, two robins on toast, oysters and a quantity of breads and cakes.”3

Joseph Willard had been commissioned a Union Army officer in 1862, spoiling for a fight, surely mindful of his family’s sturdy patriotism. An ancestor joined the Boston Tea Party in 1773, and the flag flown over Fort McHenry in the War of 1812 was called the “Bradley Flag” for another forebear, who had persuaded Congress it was about time to add two more stars and stripes to the first thirteen in honor of Kentucky and Vermont, the Willards’ birthplace. The flag is now in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

A lavish ball attended by 1,800 guests in honor of British minister Lord Napier bought prestige to Willard’s Hotel in 1859.

Library of CongressHenry Willard had been invited to Washington in 1847 to try his luck running a hotel that Charles Dickens described simply as “a long row of small houses” built in 1816 at Fourteenth Street and Pennsylvania Avenue.4 Willard was 25, with some hotel experience back home in Vermont and a fine reputation earned as “landlord, caterer, steward, or what you may name it” on a sleek Hudson River steamboat, the Niagara.5 By 1860 he had accomplished what he had set out to do: own a first-class hotel and make money. It had not been easy. Washington was far from a tourist attraction in those days; Congress, when in session, provided most of the business. “I don’t know how I shall get through,” Henry wrote to Joseph affectionately in July 1852. “I hope well but I occasionally have the blues.”6 Of the New Englanders who ran most of the country’s better hotels at that time, Henry was special, “meeting his guests as they alighted at the hotel from the stage,” reminisced Ben Perley Poore, a veteran Washington journalist. At dinnertime, “Mr. Willard stood at the head of the dinner table wearing a white apron and carved the joints of meat, the turkeys, and game.”7 Before dawn, Henry was down at the Central Market selecting the best for what he would serve in his dining room that evening.

After trying his luck at the Astoria House in New York City, Joseph had gone west to get rich in California, without letting friends know. His spunky mother, Susan, scolded her four sons in one of her colorful letters tempting them to return home with visions of homemade beer, maple syrup, and sleigh rides. Henry complained in his letters to Joseph that another brother, Edwin, his current partner at Willard’s, was “so unpopular everyone complains. . . . When once we get clear of him, we will make a new start. . . . Should you leave California, you can at any time join me in the hotel. We could make a mighty strong team.”8

Joseph did join Henry in Washington, and together they soon celebrated a major remodeling of the hotel. Years later, after many family squabbles over the Willard’s future—one settled finally by the Supreme Court in 1892—Henry praised Joseph guardedly as “the office man, the rooming clerk and perhaps his bright spot was to please the guests. He would send a man away happy who yet thought himself overcharged.”9 By 1880, the Brooklyn Eagle estimated, Joseph was worth between $7 million and $10 million, from shrewd real estate investments with his portion of the hotel’s profits; Henry was worth $1.5 million, and another brother, Caleb, also in the hotel business in Washington, $1 million.10 Edwin had died in 1863.

This sketch shows Joseph Willard giving a receipt to the Japanese treasurer for $96,000 entrusted to his care.

Library of CongressIn 1859, the hotel’s reputation was solidified by a triumphal farewell dinner and ball, for 1,800 guests, in honor of the departing British ambassador, Lord Napier. This paved the way for the Willard’s selection to host the “embassy” from Japan. It was a delicate assignment, as the seventy-seven members were the first to travel out of a Japan tightly guarded for centuries against contact with most of the Western world. Given their almost certain xenophobia, the best impressions must be made if the critical commercial relations coveted by the United States were to be established.

Benjamin Brown French, a longtime player in Washington’s political scene, witnessed the arrival of the embassy on May 13, 1860. He was shocked. “To think of a hundred men coming all the way from Japan, to bring a treaty & to see [the treaty box] ignominiously riding on top of an omnibus from the Navy Yard to Willard’s—ye-Gods and little fishes, it is too—too bad. It is, however, safe, I presume.”11

It was safe indeed. “The United States–Japan Treaty of Commerce and Friendship,” signed in Japan in 1858 by the American envoy, Townsend Harris, was the result of two years of tough negotiations with the wary Japanese. The celebrated treaty itself was encased in a red Moroccan leather box “roughly the size of a doghouse.”12

For the Japanese, the Willard’s mirrors, piano, gaslight, running water, and toilets were wonderful...Some of the Japanese visitors thought it was more impressive than the White House.

All went well for the Japanese at the Willard. Henry’s wife, Sarah Bradley Willard, wrote to her father a few days after the embassy arrived:

"Henry stood at the door to receive them, and it was pleasant to see their delighted faces as they stopped after ascending the steps to view the immense crowd and display of military. . . . Henry says they are as easy people to take care of as need be. Eat rice by the bushel and quantity of eggs, besides some meat and confectionery. Yesterday I think more than forty dozen eggs consumed. . . . They all appeared very gentlemanly and not in the least embarrassed but the physicians look dreadfully with their heads entirely shaved. . . . Their dress is very sober but I imagine rich material." 13

For the Japanese, the Willard’s mirrors, piano, gaslight, running water, and toilets were wonderful. The hotel would remain among the first to try the latest conveniences and attractions, including the telephone in 1878, the first moving-picture show in town in 1897, and air-conditioning in 1934. Some of the Japanese visitors thought it was more impressive than the White House.

The Japanese evidently had not made much use of material at their Institute for the Study of Barbarian Books to familiarize themselves with what they were about to encounter. Their reactions ranged from astonishment to revulsion. As they watched couples dance, one remarked, “We began to doubt whether we were not on another planet.”14 Another wrote, “The people of the whole country are Roman Catholic. The principal object of their worship is a naked man of about forty nailed through the hands and feet to a cross, and whose side is pierced.”15 Congress in session reminded them of a Japanese fish market.

A few envoys seemed more able to comprehend the individualistic qualities of American society. But on the whole, the scholar Masao Myoshi concluded after reading their travel diaries that most of the information they took back to Japan with them was “overly random and mostly useless,”16 and in fact may have led to a warped conclusion that military and economic might were what mattered as Japan ventured into the modern world. Most of the delegates faded into obscurity, but four met with violent deaths, having bet on the wrong side in the political turmoil of nineteenth-century Japan that led to the overthrow of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the establishment of Meiji rule: two were beheaded, and two disemboweled themselves.

The May 25, 1861, edition of Harper’s Weekly featured a dramatic depiction of a fire that began at a clothing store adjacent to the hotel with the caption “Willard’s Hotel, Washington, Saved by the New York Fire Zouaves.” The Zouaves assisted the D.C. fire brigade, forming human pyramids to compensate for a lack of ladders, and were led by Elmer Ellsworth, who would become the first Union casualty of note in the Civil War.

The White House Historical AssociationHandling the Japanese embassy’s three-week stay turned out to be a trial run for the next challenge—coping with the hordes swarming into town in 1861 for the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln, the first Republican president and the first born west of the Appalachians. Lincoln had finally been convinced that his life would be endangered if he were seen as he passed through Baltimore. So he slipped into Washington unnoticed, at dawn, and would regret the ridicule his secret arrival prompted. Lincoln already knew the Willard. As a one-term congressman from Illinois, he had met there in 1849 to help organize Zachary Taylor’s inaugural ball. He, Mary, and their three boys had for a short time tried living in cramped quarters at Mrs. Ann Sprigg’s boardinghouse on Capitol Hill, the usual accommodation at that time for everyone from Supreme Court justices to lowly representatives from the sticks. Lincoln would not have seen much change in the capital’s seedy appearance. “The same rude colony was camped in the same rude forest with the same unfinished Greek temples for workrooms and sloughs for roads,” noted Henry Adams in 1860, on his first visit in a decade.17

By 1861, it was almost a given that the president-elect would stay at the Willard before his inauguration. The tradition of the Willard as “The Residence of Presidents” had taken a while to establish, but it has endured. A worried Henry had written to Joseph in 1852, “Should I be fortunate enough to get [the president-elect] at my house, I can do good business and meet all my engagements. I am acquainted with Franklin Pierce and heretofore, he has always stayed at our house. Should he be president, I think that Post Office [for Joseph in San Francisco] could be had.”18

That last comment foreshadowed just one challenge Lincoln would face in his ten days at the Willard. Henry knew there would be a tremendous turnover of jobs with the change of administration, and soon passes had to be issued to control the crowds clamoring for Lincoln’s patronage, their share of the “loaves and fishes” Henry had earlier proposed for Joseph.19 The Willards had prepared for the onslaught with 475 additional mattresses laid out in the corridors and public rooms. even so, there was not enough room. One late arrival was “reduced to the pitiable extremity of asking permission to sleep on the steps of the front door, every foot of the inside of the house being filled up with the inaugural individuals.”20

President-elect Abraham Lincoln stayed at the Willard prior to his inauguration. Thomas Nast sketched this scene in the lobby of Lincoln sitting before the fire.

Library of CongressLincoln and his family had a comfortable suite on the second floor. The problem of his perpetually aching feet was solved quickly with typical Willard ingenuity. In the rush to conceal his arrival in Washington, Lincoln had forgot his bedroom slippers. But Henry’s wife had just knitted a colorful pair for her grandfather, who had similarly big feet. Lincoln borrowed them for the duration of his stay at the hotel. In sad contrast to all the attention paid to her husband at the Willard, Mary Lincoln’s ostracism there by the society ladies of Washington was the first of many cruel disappointments she would encounter as first lady.

When the anguished president-elect left Springfield, Illinois, on a rainy day in early February, he had observed, “I leave . . . with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington.”21 Now, at the Willard, he had still not secured the acceptance of several key cabinet members and, in an early test of his brinkmanship, would not even have William Seward’s agreement to be his secretary of state as the inaugural parade left the hotel for the Capitol. Seven southern states had already left the Union, and those still in it were also meeting at the Willard with Union representatives in a desperate effort to reach a compromise that would keep what was left of the Union together. Lincoln was not alone in thinking that the so-called old gentlemen’s convention had little chance of success.

The writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, who visited Washington in 1862, observed that “Willard’s Hotel could more justly be called the center of Washington and the Union than either the Capitol, the White House, or the State Department. . . . You are mixed up here with office seekers, wire pullers, inventors, artists, poets, editors, Army correspondents, attaches of foreign journals, long-winded talkers, clerks, diplomatists, mail contractors, railway directors—until your identity is lost among them.”22 One wag joked that there were so many VIPs at Willard’s that “a gentleman passing by threw his stick at a dog. The stick missed the dog but hit six generals.”23

Willard’s Hall, c. 1861, built in the back of Willard’s Hotel, was rented out for concerts and balls during the week and served as a worship hall on Sundays.

Library of CongressThe Willard did its utmost for the war effort, as it would for the two world wars of the twentieth century. Thirty bootblacks were hired to scrape muddy boots, and several thousand meals a day were served. Henry later told his son, “Soldiers would arrive from the field very late at night or early in the morning, and they would march out to the inner courtyard where there was a fountain of crystal water, to refresh themselves by washing their dusty hands and faces.” (Before the war, he had perfumed the water with sprigs of mint).24 If the Willard’s war bulletin board posted good news, however inaccurate, an impromptu procession formed up in front of the hotel and marched to band music to the White House.

Once Lincoln’s secretaries John Nicolay and John Hay had settled in at the White House, they went down to Willard’s for their “daily bread”25 and the latest gossip. Lincoln used the Willard as his favorite “carryout,” having “prog” sent over, reported journalist Noah Brooks.26 Lincoln could have asked the White House cook for whatever he wanted, but he was too preoccupied to care. An apple at the Willard before he went to bed had been enough. Mary Lincoln tried to inveigle her husband into eating properly by serving the few dishes he liked at breakfast or dinner, with diverting guests. She wrote a friend, “I consider myself fortunate, if at eleven o’clock, I find myself, in my pleasant room & very especially if my tired and weary Husband is there . . . to receive me and to chat over the occurrences of the day.”27

Witness to the American drama playing out every day at the Willard, William Howard Russell concluded that “the great pile of the Willard’s Hotel probably maintains inside more scheming, plotting heads, more aching and joyful hearts than any other building of the same size in the world.”28 There was John Wilkes Booth, unsettling Julia Dent Grant by glaring at her in the hotel dining room on the very day of Lincoln’s assassination. There, too, was the philandering future General Daniel Sickles, who shot his wife’s lover not long after the two were observed in intimate conversation in the Willard ballroom. He would be acquitted on the grounds of an innovative defense, temporary insanity.

Antonia Ford, depicted in a Civil War period newspaper as a rebel spy, spent several months in prison for her efforts on behalf of the Confederacy. Her release was obtained with the assistance of her future husband, Joseph Willard.

Library of CongressPerhaps the most poignant drama involved the proprietor Joseph Willard himself, who fell in love with a passionate rebel. In one fanciful version of the story, Antonia Ford went into battle disguised as a soldier and was captured by Major Willard. The two did meet when he was billeted in her Confederate family’s home in Fairfax Court House, in northern Virginia, where she was using her wiles to collect information for the Confederate Army, once riding through a stormy night to deliver vital information to General J.E.B. Stuart that affected the outcome of a major battle. Later accused of aiding in the capture of a Union general, horses, men, and supplies by guerrilla and family friend Colonel John S. Mosby, Antonia Ford was arrested and confined to Old Capitol Prison in Washington. (On hearing of this episode, Lincoln remarked he could spare the general but not the horses.) Smitten Major Willard obtained Antonia’s release after a few months. Antonia wrote, “It seems I was literally thrown into your arms by a power above us. I call it Destiny; I think it has a prettier sound than fate.”29

On New Year’s Eve, 1863, Antonia wrote to Major Willard that she would marry him “when you are at liberty to marry. But loving you as I do I couldn’t urge you to do what I know to be wrong,” for Joseph already had a wife, Caroline.30 He had resigned his commission, she had taken the oath of allegiance to the Union, and eventually a divorce came through. Antonia teased the impatient major that he “ought to be willing to be a perfectly free man for one week. Why such a hurry to enter bondage again?”31 They married on March 10, 1864; he was eighteen years her senior. She died just seven years later. The diary Joseph continued to keep after the war noted little but the anniversaries of their wedding, Antonia’s death, the loss of two infant sons—Charles and Archie—and his overweening love for the son who lived, Joseph Edward. Scores of Antonia’s letters, her schoolbooks, pieces of her embroidery, pressed flowers, and calling cards—Joseph Willard treasured every conceivable memento.32 As he became increasingly reclusive and wealthy, Henry Willard became a leading businessman and philanthropist.

A view of the Willard at Fourteenth Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, c. 1900. The building boasts a Parisian taste, which it has kept.

Library of CongressThe Willards worried about future business once the war ended in April 1865, but it boomed during the Reconstruction Era, followed by the profligate Gilded Age that one of the Willard’s regulars, Mark Twain, had given its name with his 1873 novel. A local paper looked admiringly on those turbulent times. “The great sight of America at such a time as the present is the crowd at Willard’s Hotel. . . . They represent not only the wealth of the nation but, emphatically, its business enterprise, and more nearly typify the class or classes to whom the cause of national advancement is indebted.”33

During the war Ulysses S. Grant had been so unimposing that he had not been recognized when he tried to get a room at the Willard.34 After the war, he held no grudge against the Willard for its initial lapse. As president, he favored a leather chair in a corner of the hotel lobby as his favorite spot to relax after work, smoke his favorite cigars, and observe the “lobbyists” working the crowd, whose epithet had slowly evolved over centuries from petitioners hanging around the anteroom, or lobby, of the British House of Commons.

Photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston captured the glamour of the Willard Hotel at the height of the Gilded Age.

Library of CongressTwain had his ups and downs with the Willard. In 1871, he was staying at a rival hotel, the new Arlington. As for the Willard, he wrote a friend, “O, my!—seventh–rate [hash-house].”35 Later, Henry Willard laid at least part of the hotel’s ups and downs over the years to the leasing out its management. “The war and fast money broke up conservative habits. Sporting men got in. The hotel had periods of renewal and prosperity afterwards.”36 Twain returned in 1906, to a majestic twelve-story “New Willard.” Joseph Edward Willard had been born in the Willard in 1865 and taken command in 1897 after his father’s death. He demolished the outmoded old hotel and built a thoroughly modern, all steel (faced with limestone), French Second empire Beaux-Arts style “skyscraper.” Ironically, that fashionable competitor, the Arlington, already losing business, was torn down in 1912 and never rebuilt. The legal and financial wrangling the Arlington suffered was a preview of the crises faced by the Willard years later.

Twain had taken to wearing white year-round, although he told biographer Alfred Paine Bigelow he would prefer brilliantly colored, flowing robes. Men in black suits “looked like so many charred stumps,” Twain said. When he discovered that an entrance to the Willard’s dining room through the hotel’s Peacock Alley would make him most conspicuous, Bigelow wrote, “I realize now that this gave the dramatic finish to his day. I aided and abetted his every evening in making that spectacular descent of the royal stairway and in running that fair and frivolous gauntlet.”37

Photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston captured the glamour of the lobby of the Willard Hotel at the height of the Gilded Age.

Library of CongressThe Willard Family Papers at the Library of Congress reveal the family’s dogged efforts—as far as the Willard was concerned—to live by their motto, loosely translated by a descendant today as “Hang In There.”38 The rebuilt hotel of 1900-1901 was a magnificent structure designed after New York’s Plaza Hotel. “Belle Epoque” Washington seemed summed up in the elegant Peacock Alley inside. “I am determined to uphold the highest standards of this historic old house,” insisted Belle Willard, widow of Joseph Edward.39 But it was not easy. The hotel saw hard use during both world wars, serving three thousand meals a day during World War II and rationing guests’ stays because of the severe housing shortage in the capital. By 1946, the family at last relinquished its hold on the property, and sold the hotel for a reported $2.8 million.

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy unwittingly put the Willard on a path to extinction when he rode down Pennsylvania Avenue in his inaugural parade and saw to his dismay that America’s “Main Street” was shabby and dilapidated. Worst of all, its historic linchpin, the Willard, had seen better days. National Press Club Board members meeting across the street on July 15, 1968, were astonished to learn that the owners were closing the Willard for good at midnight. The reporters raced over for one last drink at the Round Robin Bar, where the National Press Club had been born in 1908.40

The Willard Hotel at the time of the First World War. The adjacent building is the Occidental, opened by Henry Willard in 1906. The Hotel Washington is seen under construction on the far left.

Library of CongressThe struggle to save the Willard lasted four times longer than the Civil War. Dark, dusty windows and empty rooms looked down on Pennsylvania Avenue. Eighteen years passed before the Willard’s third reincarnation arose. Some wanted to replace it with an office building; others proposed a huge “National Square” in its place. Just as lines of cavalry, artillery, and infantry had once converged at the Willard’s strategic corner on their way to war, so the lines of battle over the Willard’s fate organized painstakingly to save it. Preservationists in and out of government and development grew more and more persistent, and individual Washingtonians fought valiantly, in one hair-raising example filing an injunction to stop demolition with just hours to spare. Public sentiment mounted, as people throughout the country came to realize that the hotel was a bridge not only to the country’s past but to their own precious memories. Where would all the ghosts go? they wondered.41

By 1986, the long struggle was over. The Willard survived as a major feature of the downtown revival that followed the riots of 1968. Under the auspices of the Oliver T. Carr Company, the walls of the old hotel’s meticulously restored public rooms talk again of the peacemakers and warriors, prizefighters and poets, explorers and journalists, moviemakers and stars of stage and screen sheltered by the Willard from its earliest days. What a testament the Willard Hotel is to the rich history that Americans, it is said, too often ignore. The roster of characters that have known it, and continue to know it, at points rivals even that of its distinguished neighbor, the White House.

A view of Peacock Alley before its restoration.

Library of Congress

An "after" view of Peacock Alley, showing the high quality of the restoration in creating an enchanting reflection of Beaux-Arts Washington.

Library of CongressJOHN QUINCY ADAMS, DANIEL WEBSTER, HENRY CLAY, and founding sons were remembered fondly by the orator Edward Everett for their nonpartisan conviviality at a banquet in 1853 celebrating the Willard’s first major expansion.

The poet EMILY DICKINSON, visiting Washington with her sister in 1855, promenaded in the Willard’s corridors and at dinner startled dignitaries with her bold and brilliant repartee.

JULIA WARD HOWE was quietly inspired to write “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” to the tune of the soldiers’ marching song “John Brown’s Body,” which she had heard while watching a regiment pass, singing, beneath the Willard’s window, in 1861.

“BABY DOE” (Elizabeth McCourt Doe) of Leadville, Colorado, held a wedding extravaganza at the Willard in 1883 when she married Horace Tabor, “The Silver King.” The Roman Catholic priest who performed the ceremony had been kept unaware of the bride’s divorce and the groom’s much more recent divorce. Baby Doe would die of cold and starvation years later in 1935 back in Leadville, protecting the defunct silver mine that had funded her palmy days.

JESSE VINCENT of Packard motor car company and E. J. HALL of Hall-Scott Motor Car Company were summoned to Washington shortly after the United States entered World War I and asked to remain in their Willard rooms until they completed a design for a new aircraft engine. They did so in five days, May 30–June 4, 1917. The Liberty engine would power Allied planes over France and contribute greatly to victory.

RAF pilot and children’s author ROALD DAHL, who wrote Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, was a familiar figure at the Willard, 1942–43 when, as a security attaché to the British Embassy, he was part of one of the largest covert espionage operations in British history.

Composer GEORGE M. COHAN often said that most of his plays were written in his favorite room at the Willard. His patriotic song “Over There” was a theme of World War I, and in 1936 he was presented with a Congressional Gold Medal for his rousing wartime music.

JEAN MONNET, the French economist, pondered in his ninth-floor office the irony that in the same hotel where Lincoln had struggled to keep the Union together he was envisioning, during World War II, the creation of a union of the warring states of Europe—the European Common Market.

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. prepared for his “I Have a Dream” speech in his room the night before the march on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, August 28, 1963.

The Willard Hotel during the renovation in 1988.

Library of CongressIn April 1789, George Washington took the oath of office in New York City. Constitutional guidelines for inaugurations are sparse, offering...

Elaine Rice Bachmann

NUMBERS 1 THROUGH 6 (COLLECTION I) WHITE HOUSE HISTORY • NUMBER 1 1 — Foreword by Melvin M. Payne 5 — President Kennedy’s Rose Garden by Rachel Lambert...

Read Digital EditionForeword, William SealeTaking the Oath of Office: The Capitol Connection, Donald R. Kennon"Not a Ragged Mob": The...

Read Digital Edition Foreword, William SealeThe Willard Hotel, Elizabeth Smith BrownsteinNotable Prominent Neighbors: Personalities of Saint John's Church, Richard F....

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly (February 1818 – May 1907)

Abigail Powers was born in Saratoga County, New York, on March 13, 1798, while it was still a frontier out-post. Her father,...

Grace Anna Goodhue was born on January 3, 1879, in Burlington, Vermont. She was the only child of Andrew and Lemira Goodhue....