Collection Weddings and the White House

From First Lady Dolley Madison's sister Lucy Payne Washington's wedding in 1812 to the nuptials of President Joseph Biden and First...

Main Content

How Long? 4 minutes

During the 1850s Japan gradually began to discard its isolationist foreign policy of sakoku (“locked country”) and began opening some of its ports to foreign trade while accepting diplomatic recognition from western nations. The U.S. and Japan signed a Treaty of Amity and Commerce in July 1858, and in February 1860 three samurai ambassadors and their entourage of 74 took a U.S. Navy frigate across the Pacific en route to Washington, where they would exchange the treaty’s instruments of ratification with the U.S. State Department. The Japanese delegation disembarked at the Washington Navy Yard on May 14, to be met by 5,000 cheering spectators; an additional 20,000 climbed trees and hung out of windows for a look as the visitors’ procession reached Willard’s Hotel.1 A big lattice-wood box containing the treaty was a particular object of fascination to the crowds. One reporter noted that on the visitors’ trip from the Navy Yard to Willard’s, “ragged urchins … boys, … dirty, black and white, poked their filthy digits into the carriage for the Ambassadors – Princes, be it remembered – to shake hands with them, while the Police, whose business it was to prevent such an insult, indolently lolled in the … rear.”2

The U.S. was less than a year away from civil war, but Congress overlooked sectional differences and appropriated $50,000 for expenses to host the mission. The Japanese visitors were stunned by American informality (Vice President John C. Breckinridge walked alone to Willard’s to invite them to visit Congress) and gregariousness (Secretary of State Lewis Cass treated them as though they were long-standing friends). Pianos, indoor plumbing, and Washington’s gas streetlamps impressed them, but they were less pleased with the food they were served, particularly rice swathed with butter and sugar.3

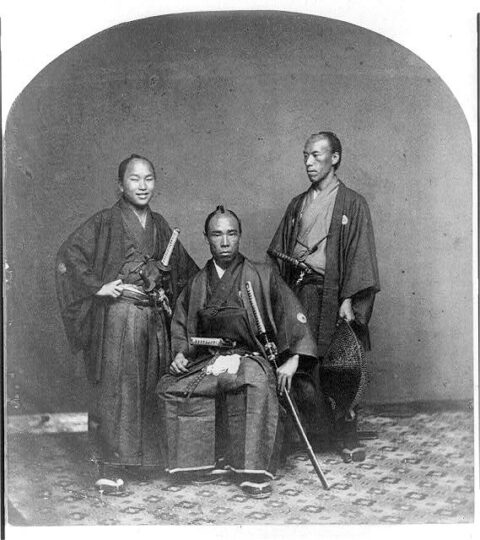

One of the Japanese mission’s interpreters, 17-year old Tateishi Onojiro, became popularly known as “Tommy” (after his childhood name Tamehachi) and quickly won fame among the press and many of Washington’s ladies. Although the rest of the envoys wore expressionless faces when out in public, Tommy unabashedly waved and blew kisses at the crowds. “Bevies of maidens gaze beneficently upon him all day,” noted one observer.4 Groups of women collected outside of Willard’s, chanting “Tommy, Tommy” until he admitted them to the envoys’ suite and charmed them with simple magic tricks.5 Children would also gather outside Willard’s and yell upward to the envoys’ rooms: “Japonee, give me a pipe, won’t you?,” “Japonee, give me a fan, won’t you?,” “Japonee, give me a cent?,” while older boys mockingly asked skyward, “Say, Jack, does your mother know you’re out?” Often their pleas for attention were met when members of the mission dropped Japanese candy wrapped inside bits of paper out of the windows.6

On May 17 the envoys were formally presented to President James Buchanan in the East Room while cabinet members, congressman and other guests swarmed in for a better view, not hesitating to stand on chairs and couches. Vice-Ambassador Muragaki Norimasa remembered Buchanan as “a silver-haired man” with “a most genial manner without losing noble dignity.”7 Buchanan exchanged handshakes and took them to the Blue Room to introduce them to his niece and White House hostess, Harriet Lane. Afterward “Tommy” Onojiro confided to a reporter, “I saw the President, splendid gentleman, and, I saw Miss Lane—Ah!”8

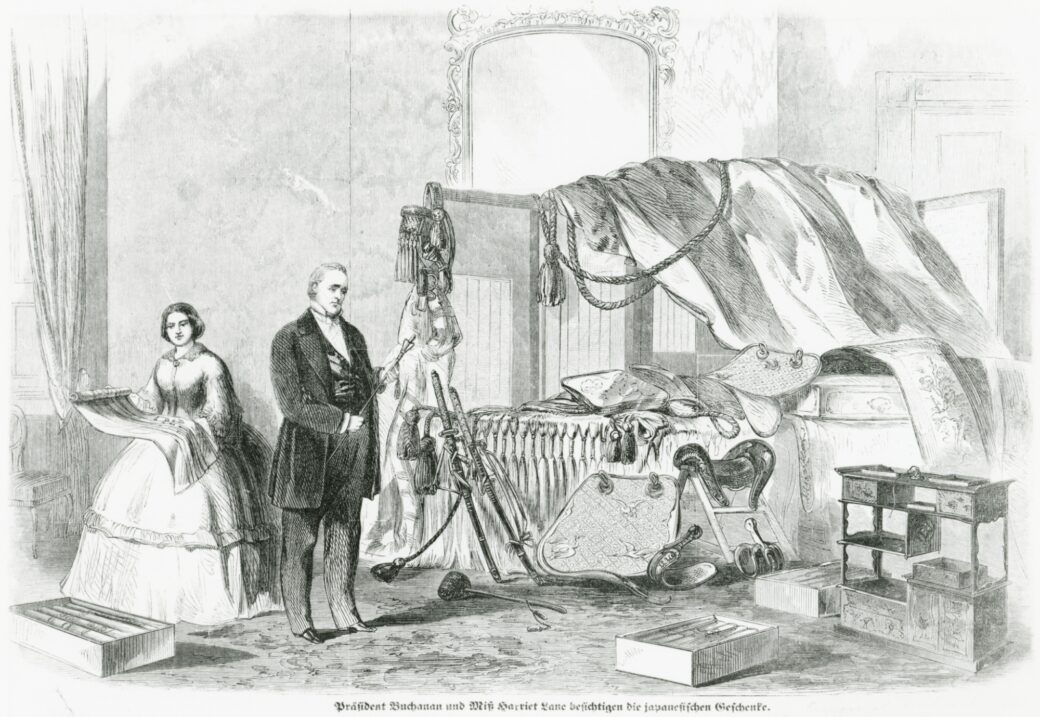

During the next ten days the diplomats heard a band concert on the White House lawn and received a personal tour of the executive mansion from Buchanan himself. They also visited Congress in session, the Smithsonian Institution, and the Navy Yard. On May 29 the envoys returned to the White House for a banquet attended by cabinet members and their wives; the menu featured chicken, halibut, ham, ice cream, lobster, pigeon, and turtle soup.9 When they made a final call on Buchanan on June 5 he presented them with gold medals specially struck to commemorate the visit. The Japanese left behind a capital city fascinated by their mysterious tonsure and attire, as well as exotic gifts such as an intricately ornate black lacquered sho-dana (shelf cabinet). The treaty ratified during their visit remained in force for the next forty years.

"Visitors from the East: President Buchanan Greets Visitors from Far Away, 1860," by Peter Waddell.

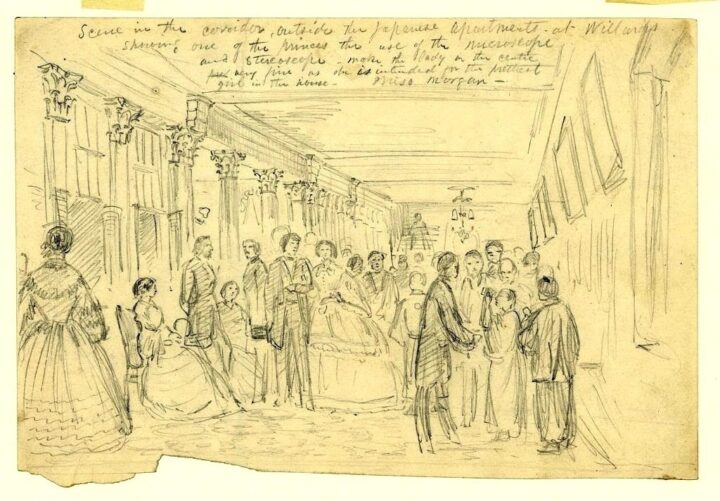

Alfred R. Waud entitled his sketch “Scene in the corridor, outside the Japanese apartments at Willards showing one of the princes the use of the microscope and stereoscope.”

President Buchanan and Harriet Lane admiring gifts from the Japanese delegation.

From left to right, interpreters Tateishi “Tommy” Onojiro, Tateishi Tokujura and Namura Moronoi, 1860.

President James Buchanan’s niece and White House hostess Harriet Lane (1830-1903), c. 1860.

From First Lady Dolley Madison's sister Lucy Payne Washington's wedding in 1812 to the nuptials of President Joseph Biden and First...

A State Dinner honoring a visiting head of government or reigning monarch is one of the grandest and most glamorous...

Native Americans hold a significant place in White House history. For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples, including the Nacotchtank and...

Many people approach the decor of their homes as a reflection of oneself. But what happens when a home's interior...

In 1961, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy resolved to make the White House a “living museum” by restoring the historic integrity of the...

From the beginning of its construction in 1792, until the 1902 renovation that shaped the modern identity and functions of the interior...

The Bellangé furniture, originally purchased by James Monroe, has adorned the Blue Room in the White House for decades. Thanks t...

The young national capital at Washington, D.C. became the center of the War of 1812 with Great Britain during the...

The collection of fine art at the White House has evolved and grown over time. The collection began with mostly...

Music is often called the universal language. It has been known to break down barriers and shape historic events in...

Biographies & Portraits

Today, the celebration of Halloween conjures images of costumed trick-or-treaters, sweets, and jack-o'-lanterns; but there was a time when All...