Collection The 2022 White House Christmas Ornament

Every year since 1981, the White House Historical Association has had the privilege of designing the Official White House Christmas Ornament....

Main Content

How a President Opened His Doors as the People's Servant

How Long? 30 minutes

In the summer of 1864, Kentuckian John Bullock called upon President Abraham Lincoln at the White House to make a personal appeal. The young Bullock took his seat in the reception area adjacent to Lincoln’s office alongside numerous other individuals, hoping for an opportunity to have but a few minutes with the nation’s leader. Uncertain if the president would even take the time to receive such an insignificant person as himself, the awestruck lad soon found himself ushered to the executive office and, there, in the presence of the president of the United States. Lincoln invited his guest to sit with him next to the fireplace, and Bullock laid out his case to the chief magistrate. He had come to seek the parole of his brother, a Confederate officer held as a prisoner of war in Ohio. The president asked Bullock if his brother would take a loyalty oath, to which he sadly replied that no, that would not happen. Lincoln stared at embers in the fireplace at great length, and Bullock concluded in his mind the certain result: his cause was lost. Bullock was shocked when Lincoln suddenly bolted out of his seat and declared, “I’ll do it,” and removed to his desk to sign on a card for the release. In the sudden turn of events, Bullock left stunned but grateful. “I left the White House with my heart overflowing with gratitude to the President,” wrote Bullock, recalling the incredible event. To Bullock, the act demonstrated “how true and genuine was Mr. Lincoln’s feeling of kindness toward others.”1

Bullock told of his meeting with Lincoln to whomever he saw. The simple visiting card from Lincoln magically granted Bullock the authority he needed to secure the release of his brother. But it had more substantial ripple effects. The Bullock family was of Kentucky stock who supported the Confederacy, and Lincoln’s act altered their perspective entirely. Their family would no longer again raise arms against the Union. Upon hearing that Lincoln was slain in April 1865, Bullock lamented that “none more truly felt genuine sorrow for the death of Mr. Lincoln than my father and his family. To each one of us it came as a personal loss.”2 One kindhearted, simple act of a servant president in his office likely spared a life and bore the favor of a family. But numerous historical accounts testify that what Lincoln did for the Bullock family was not uncommon. Throughout his presidency Lincoln’s open office door and remarkable accessibility time and again had a powerful and personal effect on the nation.

A recreation of President Lincoln's office in the 2011 painting The Visit: A War Worker Calls for a Favor, Late 1862. Artist Peter Waddell meticulously researched the details using period illustrations and written documents as references. From the mass of details in Waddell’s painting comes one mystery—the desk (upper right) in front of the doorway. This door, often spoken of, gave access to a corridor the president ordered cut through the adjacent room to allow him to pass unseen to the family quarters. Although graphic documentation all agrees on this location, one wonders how Lincoln accessed his corridor with the desk so placed.

White House Historical AssociationAt the onset of his presidency in 1861, few imagined this effect, including Lincoln himself. As he took office he found himself vilified by half a nation in rebellion, with the majority of the rest of the country at best apprehensive about his ability. When in March 1861 outgoing president James Buchanan showed Lincoln the executive office, Lincoln was so deep in anxious thought of the overwhelming weight and power of the office that he had not heard a word of anything Buchanan said there.3

Some administrative coaching may have aided the new chief executive, who had no prior executive experience to tout. Although Lincoln was a sagacious and eager study, early on most in his cabinet found him lacking and expressed little confidence in his leadership abilities. It did not aid Lincoln’s standing among his executive department heads when he failed to conduct regular cabinet meetings in his first months of taking office.4 Eventually Lincoln convened the cabinet more regularly, holding meetings on Tuesdays and Fridays, with the office door carefully guarded from visitors or the press.5

The executive office, as it was often then called, Lincoln coined as simply “the shop,” or even more unpretentiously as “this place.”6 It was an office that complemented the humble nature of its chief executive. In 1861 one of Lincoln’s secretaries, William O. Stoddard, described the room as having “an old-time and half-faded look,” not altered since the days of Andrew Jackson thirty years prior.7

The “shop” occupied the near southeastern upstairs corner of the White House; it was about 29 by 24 feet in size. The centerpiece of the room’s furniture consisted of a large, very plain, oak table—the “council table” as it was called—covered with a cloth around which the cabinet sat when it held its meetings. “Any number of notable men have sat around it,” Stoddard noted, “discussing the affairs of the nation and of the world.”8 Lincoln often piled the council table with books, documents, and maps when the cabinet did not meet. Above the table hung a bell cord by which he alerted his secretaries John Hay or John Nicolay when their service was needed. A glass-globed gaslight was suspended from the ceiling. At the south end of the room, between the two windows, stood another table, at which Lincoln sat in a large armchair and used as his desk. In the southwest corner stood another upright mahogany desk so battered that Stoddard quipped it might have been salvaged “from some old furniture auction.”9 Pigeonholes in that desk served as Lincoln’s filing cabinet. Two other, larger chairs and two sofas were spaced within the room. Stacked against the walls were numerous books—chief among them the Bible, a volume of Shakespeare, and the United States Statutes. On the walls in frames hung several military maps; other maps were spring-loaded like window shades. Here the positions and movements of troops could be followed. Above the fireplace mantel on the west wall hung an old and discolored oil painting of General Jackson and a photograph of John Bright, English member of Parliament. A mantel clock ticked away the seconds of time. Doors opened to the main hallway and to the secretary’s office. Lincoln had a wall built in the room west of his office so that he could walk unmolested from his office to the private living quarters.10

From the large window nearest his desk, Lincoln could gaze out onto the South Lawn into the distance, as Washington was far from the sprawling city it is today. An unfinished Washington Monument, the Smithsonian Castle, and the Potomac River basin dominated the cityscape. White tents of soldiers’ camps dotted the hills within and around the city. Across the Potomac River stood Arlington House, the home of Robert E. Lee. Just beyond in Alexandria atop a hotel, a rebel flag waved in defiance of the federal government.11 That Confederate flag flying within sight of the White House bothered Lincoln immensely, and his friend Colonel Elmer Ellsworth volunteered to remove it from the building, only to be gunned down in his heroic act. When given the news of the death of Ellsworth—the first casualty of the Civil War and whom Lincoln called the “greatest little man I ever saw”12—the president stared out the White House library window looking toward Alexandria, covered his face in his hands, and wept bitterly. Those gathered felt moved at the emotion “in such a man, and in such a place.”13

The death of the young Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, who was shot as he attempted to capture a Confederate flag flying in Alexandria on May 24, 1861, deeply grieved President Lincoln. Ellsworth was a colonel in the National Guard Cadets in Chicago. He became close to Lincoln during the 1860 campaign, vowing to defend the candidate against harm, and he moved to Washington with the Lincolns. The president ordered his remains brought to the White House, where he lay in state in the East Room, beneath a wreath of flowers woven by Mary Lincoln.

Library of Congress

An artist's rendition of the funeral for Col. Elmer Ellsworth. The death of the young Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, who was shot as he attempted to capture a Confederate flag flying in Alexandria on May 24, 1861, deeply grieved President Lincoln. Ellsworth was a colonel in the National Guard Cadets in Chicago. He became close to Lincoln during the 1860 campaign, vowing to defend the candidate against harm, and he moved to Washington with the Lincolns. The president ordered his remains brought to the White House, where he lay in state in the East Room, beneath a wreath of flowers woven by Mary Lincoln.

Library of CongressMany witnessed Lincoln in similar situations, staring out his office window and pondering the nation’s fate. After a few minutes absorbed in thought, he would turn to the council table or to his desk where he would perform—in Stoddard’s words—his “political and military miracles” for the many that requested his aid.14

Those entreaties for miracles were many. This was an era in which anyone could literally walk right into the White House and request a private meeting with the president. If willing to wait long enough, one could likely meet him. Lincoln received everyone from the most important members of Congress, to his generals, to newspapermen, to the private soldier and the humblest citizen. Rules of precedence held that cabinet members and ranking army officers were generally granted prompt admittance. Members of the House would be received in order of their arrival, although Dr. Anson Henry sarcastically quipped that “it is no uncommon thing for Senators to try for ten days before they get a private interview.”15 Sometimes there might be a great crowd of people waiting their turn in the anteroom adjacent to Lincoln’s office. There in his shop, day after day, and often late into the night, Lincoln sat, listened, talked, and decided. As Nicolay noted, “Lincoln seldom if ever declined to receive any man or woman who came to the White House to see him.”16

All varieties arrived to see the president: mothers who wanted to have their sons or husbands paroled from the army, sisters or wives of deserters who wanted reprieves for them, brothers of wounded soldiers who wanted their release from service, ambitious men who wanted military or political offices, newspaper editors seeking an interview, self-appointed advisers who wanted to be listened to, or people who just wanted to personally meet the president of the United States. Of all the visitors, White House guard William Crook remarked that the latter group was the “most persistent and unreasonable.”17 Hay bemoaned the office-seekers who had “invaded and overrun” the White House and who “come in at daybreak and are still coming in at midnight.”18

A clipping from the July 29, 1862, Sandusky Daily Commercial Register describes the scene at the White House when one of President Abraham Lincoln’s visitors stayed a bit too long. The press was often critical of the president for allowing so much of his day to be taken up by the public during wartime.

Sandusky Daily Commercial RegisterLincoln attempted to both attend to other business and receive the throngs twelve hours a day. His secretaries Hay and Nicolay sought to persuade the president to adopt some systematic rules for visiting, limiting reception hours to 10:00 a.m.–1:00 p.m., but this limit operated in theory only. They found their boss would disregard those arrangements as fast as they were made.19 Hay recalled, “The president was always the first to break down barriers” in his contact with people and “disliked anything that keep people from him who wanted to see him.”20

Stoddard noted the Executive Mansion was “packed with human beings,” recalling that “the throng of eager applicants for office filled the broad staircase to its lower steps, the corridors of the first floor, and the famous East Room. The president’s kindly nature led him to surrender too much of his time and strength to private hopes and ambitions. He had hardly time left him to eat and sleep.”21 Crook observed that “the White House has never, during my forty years’ service, been so entirely given over to the public as during Mr. Lincoln’s administration.” Suspicious of their motives, Crook asserted, “The house was filled . . . with all sorts of people, of all varieties of political conviction, who felt, according to the temper of the time, that they had a perfect right to take up the President’s time with their discourse.”22 Nicolay grumbled that he could not walk down the street without “almost every man, woman and child I meet—whether it be by day or night,” requesting a meeting with the president.23

Many, especially the press, rebuked Lincoln for this excess imposition upon him during wartime. The Washington Daily National Intelligencer lamented that the demands on Lincoln’s time from visitors was “one of the tribulations which must greatly add to the fatigues of office at this juncture, that our amiable President has to give so much of his time and attention to persons who apparently [have] no business of their own.”24 The New York Times derided the president, writing: “Mr. Lincoln owes a higher duty to the country, to the world, to his own fame, than to wither away the priceless opportunities of the Presidency in listening to the appeals of the competing office-hunters.”25 One observer noted that Lincoln’s chief trouble in his entire presidency came from the stream of applicants for political office.26

Lincoln was indeed annoyed by some of the demands. When a group called on him seeking an appointment to the Sandwich Islands for a friend for health reasons, Lincoln sarcastically responded, “Gentlemen, I am sorry to say there are eight other applicants for the place, all sicker than your man.”27 A man of stature once visited to ask if the president would lend his name to his business project, only to have Lincoln spring from his seat with an emphatic “No!” and berate him, “You have come to the wrong place; and for you and everyone who comes for such purposes, there is the door!”28 When on a crowded visitor day Lincoln’s physician diagnosed the president with a contagious case of smallpox, Lincoln responded good-naturedly that he finally had something that he could give everybody.29

But even among the peskiness of office-seekers and those seeking favors, Lincoln generally relished opportunities to communicate in his office with the average citizen. He found it difficult to abide by his own visiting hours because he liked the “plain people,” as he called them, and believed that his task of governing depended upon their satisfaction.30 Hay observed that Lincoln gained “something of cheer and encouragement” from these visits. Lincoln listened “with the eagerness of a child” over stories and battle accounts, and delighted in witty talk.31 He felt the everyday American deserved a chance to talk personally with the president in his office. “They do not want much,” he asserted, “and they get very little. Each one considers his business of great importance and I must gratify them. I know how I would feel in their place.”32

White House guard William Crook considered office-seekers to be the “most persistent and unreasonable” group of President Lincoln’s many visitors. This detail of a wood engraving made for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper of April 6, 1861, shows a group of office-seekers gathered in the White House Entrance Hall in hopes of meeting with President Lincoln.

White House Historical AssociationLincoln made himself at home in his “shop,” and Hay observed that visitors who met Lincoln for the first time were immediately struck both by the plain room and by the president’s freedom “from pomposity.”33 Of the room’s simplicity Lincoln stated, “There is no smell of royalty about this establishment.”34 Accordingly, Lincoln’s style reflected that simplicity. Lincoln abhorred titles and would often say, “Call me Lincoln; ‘Mr. President’ is entirely too formal.”35 In the course of conversation with guests, it was not uncommon for Lincoln to swing his legs over his chair or to stretch out on his sofa with his hands folded over the top of his head.36 The lack of formality and etiquette surely shocked those who presented themselves in their Sunday best, only to meet a president in his slippers.37

Meeting a disarming president without pretensions in his White House chambers must have proven surprising, but inviting, to the common, everyday Americans. Disdaining social formalities, Lincoln, noted Stoddard, “looked upon whomever he met as no more or less station in life than he was.”38 Stoddard marveled at how the president greeted mountaineers from east Tennessee like brothers. “He is one of them, really,” marveled John Hay. “I never saw him more at ease than he is with these first-rate patriots of the border.”39

On one occasion a southern woman from South Carolina called upon the president out of curiosity, harboring prejudices that Lincoln was a “terrible monster.” After listening to him for a few minutes, she blurted out, “Why Mr. Lincoln, you look, act, and speak like a good hearted, generous man.” Lincoln questioned her, “Did you expect to meet a savage?” She retorted, “Certainly I did, or even worse.” Clearly changing her opinion of Lincoln and his intentions for the South, she remarked, “I am glad to have met you.” From this single experience in Lincoln’s office, she became a loyal supporter of the president.40

John Nicolay’s daughter relayed that among Lincoln’s numerous callers it was with “women in distress,” particularly “women in the humbler walks of life, that his kindness was most marked.”41 In 1863, a lady convulsed by sobs visited the White House for several days hoping for a chance to see the president and ask for the release of her son from soldier duty. As the last person waiting in the anteroom one day, she was presented to the president. As he stood before the fireplace, hands clasped behind his back, staring at the floor listening, she relayed how her husband was gone and her other son had died in battle. She pleaded to Lincoln to write for the release of her remaining son to come home to her. Lincoln softly uttered, “I have two and you have none.” With that, he walked to his writing table, took up a pen, and ordered the release of her remaining son. James Speed, who witnessed the event, watched the woman stand by him as he wrote “and with the fond familiarity of a mother placed her hand on the President’s head and smoothed down his tangled hair.” Speed detected, “Human grief and human sympathy had overleaped all the barriers of formality, and the ruler of a great nation was truly the servant, friend, and protector of the humble woman clothed for the moment with a paramount claim of loyal sacrifice.” The president rose, handed the note to her, and hurried from the room followed by the blessings of an overjoyed mother. Speed recalled, “A volume could not describe the suppressed emotion or the simple eloquences of the act.”42

Commenting on the thousands of people that Lincoln opened his door to in his four years, the newspaperman Francis Fisher Browne astutely observed, “These meetings and interviews with people devoid of ceremony revealed the man in his true character and endeared him greatly to the popular heart.”43 In Ward Hill Lamon’s words, “Lincoln believed he was the people’s servant, not their master.”44

It was observed that President Lincoln’s “kindness was most marked” when he met with women in distress. Many mothers, wives, sisters, and daughters traveled to the White House to plead for their loved ones who were in trouble—frequently jailed for desertion or held as prisoners of war. This note is an example of a reprieve granted by the president: “Let this man take the oath of Dec. 8, 1863 & be discharged. ALincoln, Dec. 29.1864.”

Lincoln Heritage MuseumLincoln experienced more difficulty in winning over newspaper editors to his side. Often reviled in print, he found the constant “fault finding of the press” against him an all-to-common occurrence.45 When a caller expressed his dismay over a harshly written negative column against Lincoln in the New York Herald, Lincoln waived it off, saying, “They are a fair specimen of what has occurred to me through life. . . . I am used to it.”46 Lincoln sarcastically likened newspapermen to a story he told of a man lost in the forest at night during a thunderstorm. The man dropped to his knees, “O Lord, if it is all the same to you, give us a little more light and a little less noise!” Lincoln wished the same from the press.47

However vitriolic the criticism thrown at the president, when it came to public dissemination and acceptance of his policies Lincoln worked the press to his advantage—especially in regards to abolition policy. By the time Lincoln had decided on a policy of emancipation in the summer of 1862, he knew well that many northerners were unwilling to approve the freeing of a great many southern slaves unless it was coupled with plans for blacks to leave the nation altogether. On August 14, 1862, just weeks before the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation, in an unprecedented move Lincoln became the first president to invite African Americans into the White House. In advance of the release of the preliminary proclamation, Lincoln welcomed a delegation of free black leaders from Washington, D.C., to his office, urging them to consider for their race voluntary colonization to lands outside the United States so they would no longer endure discrimination by whites. He told them, “Your race is suffering, in my judgment, the greatest wrong ever inflicted on any people. But even when you cease to be slaves, you are yet far removed from being placed on equality with the white race.” Encouraging emigration for blacks to Central America, he told them, “It is better for us both to be separate.”48

Days after the meeting, one of the delegation wrote to Lincoln, “We were entirely hostile to the movement until all the advantages were so ably brought to our views by you. . . . It is our belief that such a conference will lead to an active and zealous support of this measure by the leading minds of our people.”49 However, the colonization plans were harshly criticized by other black leaders, chief among them Frederick Douglass.

But Lincoln was clearly not as concerned about the reaction of the meeting from black leaders as he was about the reaction of whites. The meeting’s entire purpose was likely to placate white fears. Not only had Lincoln assembled leading blacks to the meeting, but also invited, among other newspapers, Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune, which had the largest circulation of any daily in the country. Lincoln’s intent was that the Tribune and other influential newspapers would record the exact transaction of the meeting—which they did—so his remarks would be dispersed widely in newspapers across the country. This meeting in his office served simply as a “press event” to ready the country for emancipation and to assuage racial fears. Lincoln succeeded in his public purpose.50

Horace Greeley, editor of the New-York Daily Tribune, supported President Lincoln’s election and pressed him for an end to slavery early in his administration. The most widely circulated paper in the nation at the time, the Tribune was invited to the press event on August 14, 1862, which was intended by Lincoln to help prepare the nation for emancipation. As the president had hoped, Greeley included an exact transcription of the event in the August 15, 1862, edition. Lincoln clipped articles from newspapers and kept one pigeonhole in his desk specifically for Greeley’s columns.

Library of CongressA week following the meeting with the delegation, Lincoln advanced his policy on emancipation by responding to an editorial in the Tribune. In mid-August, in a piece entitled, “The Prayer of Twenty Millions,” Greeley had indicted the president’s weakness on the slavery issue. Now, addressing Greeley as “an old friend,” Lincoln answered the charge, asserting “what I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union.”51 As Lincoln hoped, the Intelligencer and other newspapers across the country picked up the story, and it was read North and South. Lincoln had again successfully used the press to expound upon his administration’s policy that any future actions on emancipation were tied to military and larger aims.52 Undoubtedly such press statements helped turn public opinion.

Lincoln experienced frustration, however, when newspapers misstated his words. When a Missouri newspaper editor called upon Lincoln, the president charged that the press “like yours . . . have persistently garbled and misrepresented what I have said.”53 In 1863, when Lincoln penned a long letter to James Conkling back in Springfield further explaining his stance on black soldiers fighting for the Union, he turned down requests for advance copies from Washington correspondents, including the Associated Press, because he felt they could not be depended upon for secrecy. Despite his rebuff, much to his chagrin the New York Evening Post somehow received a copy and printed the letter word-for-word before it was made public.54

Noting the press’s “power for both good and evil,” Lincoln blamed newspapermen and editors and for contributing to public sentiment against the administration.55 After the 1863 New York draft riots, Joseph Medill of the Chicago Tribune led a delegation to call upon Lincoln at the White House. The president listened patiently, then huffed, “You ought to be ashamed of yourselves.” Shaking his finger at the delegates and berating them, he retorted, “You and your Tribune have had more influence than any paper in the Northwest in making this war. You can influence great masses, and yet you cry. . . . Go home and send us these men.” Medill admitted he was whipped and went home to raise more troops.56

Editors all over North sent their newspapers to the White House, hoping the president might read their editorials, though likely the papers were first distributed to staff, and most failed to reach Lincoln.57 Stoddard said Lincoln cared little for newspaper opinion and that the president claimed he “knew the people so much better than the editors did.”58 Although Lincoln never saw many of the harshest criticisms against him, he did clip certain articles that he read, filing them in his upright office desk under the heading “villainous articles.”59 Lincoln even kept a pigeonhole specifically for Greeley.60 In part because Lincoln perceived that few newspapers treated him fairly, the president gave great favor to editor John W. Forney and his Washington Daily Morning Chronicle, which began publication in 1862 and many regarded as a mouthpiece of the administration. Both Hay and Nicolay often wrote for it.61

Instead of simply writing to the president, many editors and publishers called upon Lincoln personally, and almost every northern journalist of prominence was a visitor in the president’s shop during the war.62 Greeley, for one, often called upon Lincoln. Journalists and newspaper editors waited in line with their cards in the anteroom to see Lincoln alongside everyone else. If a subject was of great interest to Lincoln, he would call the reporters into his office to “skirmish” with them or go to anteroom and explain the issue in detail.63 Welles resented the press’s intrusion into Lincoln’s shop, complaining that Lincoln “permits the little news-mongers to come around him and be intimate.”64 Indeed, Lincoln leaked tidbits and allowed personal contact with newspaper men whom he trusted, such as the Sacramento Daily Union editor Noah Brooks, familiar to Lincoln from his Illinois days. Forney of the Chronicle and Simon Hanscom of the Washington National Republican visited the White House and received the ear of the president perhaps more than any other men in journalism.65

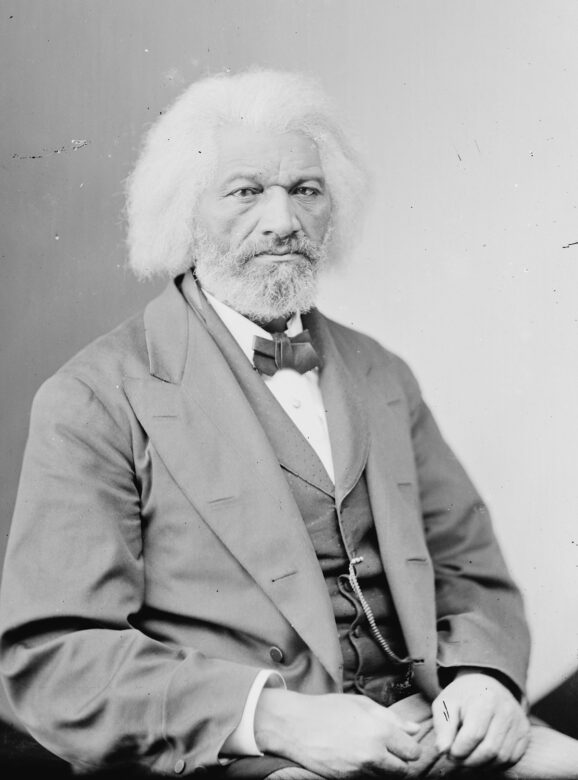

Visitors to Lincoln’s office were often struck by the president’s appearance and welcoming greeting. The first nationally distinguished African American invited into the White House, Frederick Douglass, recalled that although he had been nervous about meeting the president, he immediately felt at ease in his presence. An article in the London South Advertiser describes the writer’s surprise at President Lincoln’s unusual height. This photograph captures the scene of the president at his desk in 1864 as so many described.

Keya Morgan Collection, lincolnimages.comAmong the stories of visitors from all walks of life whom Lincoln received, particularly moving is the account of the first meeting between two giants of the nineteenth century who emerged from different backgrounds. As the first nationally distinguished African American ever invited into the White House, the former slave Frederick Douglass felt trepidation when he first met Lincoln in 1863. He later recalled, “I was somewhat troubled by the thought of meeting one so august and high in authority . . . and had never spoke to a President of the United States before. But my embarrassment soon vanished when I met the face of Mr. Lincoln.”66

Deeply conscious that he was a black man who in previous administrations would have been unwelcome in the president’s office in the White House, Douglass recollected:

"I was never more quickly or more completely put at ease in the presence of a great man, than in that of Abraham Lincoln. He was seated, when I entered, in a low arm chair, with his feet extended to the floor, surrounded by a large number of documents, and several busy secretaries. The room bore the marks of business, and the persons in it, the president included, appeared to be much overworked and tired. Long lines of care were already deeply written on Mr. Lincoln’s brow, and his strong face, full of earnestness, lighted up as soon as my name was mentioned. As I approached and was introduced to him, he rose and extended his hand, and bade me welcome. I at once felt myself in the presence of an honest man—one whom I could love, honor and trust without reserve or doubt. Proceeding to tell him who I was, and what I was doing, he promptly, but kindly, stopped me, saying, 'I know who you are, Mr. Douglass; Mr. Seward has told me all about you. Sit down. I am glad to see you.'”67

That auspicious greeting began the first of several grand meetings at the White House between the two leaders.

The first nationally distinguished African American invited into the White House, Frederick Douglass, recalled that although he had been nervous about meeting the president, he immediately felt at ease in his presence. An article in the London South Advertiser describes the writer’s surprise at President Lincoln’s unusual height.

Library of CongressFrom his shop, Lincoln met with countless individuals tending to their needs. There he wrote hundreds of letters and other correspondence. There he poured over maps and reports of the numbers of dead, wondering where he would get enough men to continue the fight. Even into evening time, he usually labored in his office, though both Stoddard and Hay recalled that frequently the tired president passed the evening in the company of a few friends “in frank and free conversation.”68 At times, Lincoln’s sons, Tad and Willie, would jump onto their father’s lap, climb on his shoulders, or lay on his couch until they fell asleep. After Willie died, Tad more frequently occupied the office for the entire evening, dropping to sleep on the floor, where Lincoln would scoop him up and carry him tenderly to bed.69

But Lincoln’s dedication to the service of his country took its toll. With all the troubling duties before him, Lincoln stated to one visitor that he was surprised that “anybody would want the office” at all.70 As a respite from the hustle and bustle of the White House, Lincoln spent hours at the War Department, where he received telegraphs from his generals. He would also increasingly retire to the Soldiers’ Home in the evenings. He did partake in an occasional carriage ride with Mary Todd Lincoln, or in a personal horseback ride. Yet the bulk of his time as president he toiled in that upstairs room in the White House, tending to duties.71

Even when Lincoln’s son Willie lay dying in February 1862, Lincoln was not gone long from his office. Stoddard observed that during Willie’s illness, “if the president left his office to visit the sick-room, it was only to return again and meet as before the hourly tribulations of his unrelaxing service of his country.”72 While he agonized personally over his dying son, Lincoln felt duty-bound not to flinch from his obligations and burdens, and returned a few rooms away to the matters of the war on which so many depended on him. He could even be found in his office the day of Willie’s funeral.73

Artist Tom Freeman’s 1999 painting envisioned President Lincoln pausing under the North Portico en route to the War Department where he received telegraphs from his generals.

White House Historical AssociationTo his detriment, Lincoln spent so much time here that he made himself a virtual prisoner in his own office.74 According to Crook, Lincoln would arrive in his office at half past nine in the morning until he went to bed “almost without cessation.”75 When Lincoln received telegrams following the 1863 Battle of Chancellorsville, which exacted heavy loss of life, Brooks observed him pacing back and forth in his office in anguish, exclaiming, “My God! What will the country say!”76 The night after that battle, Stoddard departed the White House at 2:30 a.m., only to still hear from Lincoln’s office the heavy footsteps from “the all but heart-broken ruler.”77 Said Stoddard, “I remember some nights when all he did was to walk up and down the room.”78

As war dragged on, friends observed that Lincoln listened with the same sympathetic patience to the requests and petitions of his visitors as always, but his hearty laugh was heard less often.79 Hay expressed that “there was little gaiety in the Executive house” as the years advanced.80 Lincoln’s retreat in his White House shop—though miles from the battlefield—never afforded an escape from the horrors of war. When a grief-stricken widow called upon Lincoln, he said empathetically, “Your experience will help me to bear my own afflictions.”81

But where he endured sorrow, Lincoln also encountered success. Whereas at the onset of his term in 1861 most of Lincoln’s own unwieldy cabinet perceived their new commander in chief as either incapable of leading or unwilling to lead, Lincoln ultimately harnessed their talents and energies, and, through many sometimes intense and heated cabinet discussions, he and his cabinet directed efforts to win the Civil War. In 1861 just months into the new term “Executive force and vigor are rare qualities; the President is the best of us.”82

It was in this very room in the summer and fall of 1862 that the cabinet wrangled over emancipation policy in some of the most tense but momentous cabinet proceedings in American history. Through several onerous meetings, Lincoln was able to convince his divided cabinet of the wisdom of the Emancipation Proclamation, hammering out a document that changed the course of the nation. Then on January 1, Secretary of State William H. Seward blasted Lincoln for having no war policy: “Either the President must do it himself, and be all the while active in it, or, devolve it on some member of his Cabinet.” Just months later, Seward wrote to his wife admitting he had erred in judgment, remarking, 1863, after greeting hundreds of guests in the annual New Year’s Day reception in the Blue Room, Lincoln slipped upstairs to his office to sign the awaited proclamation. Sitting at the cabinet table, he paused and prophetically declared to Seward and a few others gathered to witness the occasion, “I have never in my life felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper. If my name ever goes into history it will be for this act.”83 Indeed, that act precipitated the eventual release of more than 3 million people from bondage.

This 1863 photograph captures the skyline that President Lincoln would have known, dominated by the Smithsonian Castle and the unfinished Washington Monument.

Library of CongressIn 1864, in one of the many times members of Congress called upon Lincoln in his office berating him for who he had or had not appointed or relieved in his cabinet or on the battlefield, Lincoln walked up and down his room patiently listening; then turning, he unrelentingly admonished his visitor—in this case, Congressman Thaddeus Stevens—“God knows I do not want the labor and responsibility of the office for another four years. But I have the common pride of humanity to wish my past four years administration endorsed; and I honestly believe that I can better serve the nation in its need and peril than any new man could possibly do.”84 Lincoln realized his own growth in the office, and how he had used his power and position for the good of the country. Voters agreed in 1864, returning him to the presidency for a second term. From his command center in the White House, Lincoln as commander in chief directed a war effort to ultimate victory and a long-desired restoration of the Union.

Nicolay noted a “deep and tranquil happiness throughout the United States” on the morning of April 14, 1865.85 Just five days following the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, Union General Ulysses S. Grant arrived in Lincoln’ s office to meet with the cabinet. Grant expressed his confidence that the final troops in rebellion would soon surrender. The cabinet heartily applauded the news, and Lincoln spoke, advocating for the rapid readmission of the rebel states. Then, in the same compassionate tone that he had so often employed with those who had come in and out of his door, the president offered with malice toward none his desire that the secessionists not be hanged. “Enough lives have been sacrificed,” he stressed.86 The cabinet cheered the leader they had come to fully respect. Following the meeting, as they left the room, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton told Attorney General Edward Bates, “That is the most satisfactory Cabinet meeting I have attended for many a long day. What an extraordinary change in Mr. Lincoln.”87 What was surely equally evident was the significant change Lincoln had brought to the nation.

Lincoln and his wife planned to attend the theater that evening of April 14. Before departing his shop for the day, he approved a petition from a Confederate prisoner wishing to take the oath of allegiance. On the petition, Lincoln scribbled simply, “Let it be done.”88 It was only fitting that among his final executive acts as president, Lincoln would once again use his modest shop in the White House as a conduit of mercy and as the people’s servant.

So much had been accomplished by one man in one room. Lincoln’s office and Cabinet Room—the shop—is now known as the Lincoln Bedroom. Its history has afforded it a unique place among the most famous rooms in America; it is a rare privilege to be invited to stay there or even be granted permission to step inside to view it. The current limited public access to the Lincoln Bedroom is ironic, considering how often the door would swing open to virtually anyone who wanted to see the president when Lincoln occupied it. To a certain extent that is understandable in this age of heightened security. But at least the quasi-sacredness of the room that served as the business space for Lincoln and other presidents has not been lost on later chief executives. “History permeates the room,” President Gerald Ford recollected. Recalling how when president he would go to the room to reflect, he reminisced, “I would sit alone. . . and I could almost hear the voices of 110 years before. When I left the room I always felt revived.”89President George W. Bush observed that the presence of Lincoln could truly be felt in the room, remarking, “It reminds me of how difficult Lincoln’s life was during his presidency.”90 Former president, Barack Obama, an Abraham Lincoln enthusiast, has said, “From time to time, I’ll walk over to the Lincoln Bedroom . . . in search of lessons to draw.”91

The Second Floor room that once served as President Lincoln’s office is now the well-known Lincoln Bedroom. A copy of the Gettysburg Address, handwritten and signed by Lincoln, is displayed on the desk in the corner. Hanging above it is the painting Watch Meeting—Dec. 31st 1862—Waiting for the Hour by William T. Carlton, which depicts slaves waiting for news of the Emancipation Proclamation. An engraving of Francis B. Carpenter’s 1864 painting, First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation, is seen reflected in the mirror above the fireplace mantel. This space where Lincoln once readily admitted visitors is not on the public tour.

White House Historical AssociationEvery year since 1981, the White House Historical Association has had the privilege of designing the Official White House Christmas Ornament....

In 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was sworn in for the first of his four terms as president of the United States....

From hot dogs to haute cuisine, U.S. Presidents have communicated important messages through food. Stewart McLaurin, President of the...

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr., the nation’s only unelected president and vice president, served thirteen terms in Congress before rising to...

The American experiment has long held the curiosity of people around the world, especially for Iain Dale, an award-winning British...

In 1821-1822, Susan Decatur requested the construction of a service wing. The first floor featured a large kitchen, dining room,...

When First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy took on the herculean task of restoring the interior of the White House, she appointed...

From First Lady Dolley Madison's sister Lucy Payne Washington's wedding in 1812 to the nuptials of President Joseph Biden and First...

Over 200 years ago, James Hoban left Ireland for America to pursue his dream of becoming an architect. Selected by President...

Since 1965, the White House Historical Association has been proud to fund the official portraits of our presidents and first ladies,...

In this first episode of 2021, White House Historical Association President Stewart D. McLaurin introduces the Association’s popular virtual program Hi...

Every year since 1981, the White House Historical Association has had the privilege of designing the Official White House Christmas Ornament....