Collection Weddings and the White House

From First Lady Dolley Madison's sister Lucy Payne Washington's wedding in 1812 to the nuptials of President Joseph Biden and First...

Main Content

The Equestrian Statues of General Andrew Jackson

How Long? 21 minutes

The Andrew Jackson equestrian statue in Lafayette Park is familiar to most of the world in its place in front of the White House in Washington, D.C. The original sculpture was erected in 1853. Thereafter the sculptor, Clark Mills, made replicas for New Orleans in 1856 and for Nashville in 1880. A fourth copy was cast as recently as 1987 for outdoor display in Jacksonville, Florida. The Andrew Jackson statue for Washington was historically significant because it was the first bronze statue cast in the country. Mills brought his enslaved apprentice, Philip Reed, to Washington while he was working on the statue, but it is unknown exactly what Reed did for this statue.

Clark Mills gained additional fame because his Jackson statue was also the first equestrian statue in world to be balanced solely on the horse’s hind legs. There is a whole literature on the supposed meaning of the position of horses’ hooves on equestrian statues. Books on sculpture often describe the hooves as symbolizing how the subject fared in battle. There are other interpretations. One recent study tells us that one raised hoof indicates the rider was wounded in battle, while two indicate the rider died in battle, and when the rider is standing beside his horse, both were killed in battle.1 A description of the Andrew Jackson statue in Jackson Square, New Orleans, suggests that the horse being shown rearing back on two legs foretold the rider’s achieving a title even higher than that of general.2 In researching the twenty-six equestrian statues in Washington, D.C., I found no relationship between the position of the horse’s hooves and the fate of the rider.

Andrew Jackson (1767–1845) was born to Presbyterian Scots-Irish immigrant parents. His birthplace is usually believed to be North Carolina, along the South Carolina line. While serving in a North Carolina regiment as a courier during the American Revolution, a teenaged Jackson was captured with his brother and imprisoned by the British army. When Jackson refused to clean the boots of a British officer, he was slashed across his head. The blow left a lasting scar and an intense hatred for the British. After studying law briefly in Salisbury, North Carolina, Jackson sought his fortune on the Tennessee frontier, to which he moved in 1787. He quickly became a successful lawyer and eventually established a plantation near Nashville, called The Hermitage. When Tennessee became a state in 1796, Jackson served as its representative in Congress, then as a U.S. senator in 1797, and finally as a judge on the Tennessee Supreme Court in 1798.3

Jackson’s military career began in 1791 when he joined the Davidson County, Tennessee, militia. He was popular with his men and quickly rose in rank. In 1802, he was elected a major general in the Tennessee militia.4 When the Creek Indians resisted white settlement in what is now Alabama in 1813, killing more than four hundred American settlers, Jackson led the retaliation with a force consisting of militia, regular U.S. Army troops, and friendly Indians. The Creeks were defeated at the battle of Horseshoe Bend in March 1814. In the resulting Treaty of Fort Jackson, the Creeks ceded their lands in Alabama and Georgia to the U.S. government, thus opening a vast territory to white settlement. It was at the battle of New Orleans, however, on January 8, 1815, that Jackson achieved greater fame. His victory there over the British was the last battle of the War of 1812, and it made him a national hero, paving the way to the presidency. Jackson was the seventh president of the United States, serving two terms, from 1829 to 1837.

A view of the equestrian statue of General Andrew Jackson by Clark Mills erected in Lafayette Park in 1853. The first bronze statue cast in the United States, it weighs 15 tons. This photograph was taken from the south in 2008.

White House Historical AssociationAfter completing his second term as president, Jackson returned to The Hermitage, where he died from medical complications at age 78 on June 8, 1845. The nation mourned “Old Hickory,” a man who, along with Thomas Jefferson, was considered founder of the Democratic Party. The creation of the equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson in Washington, D.C., was a direct expression of the nation’s reaction to his death. In July, John L. O’Sullivan of New York, editor of the United States Magazine and Democratic Review, called for a private subscription to erect a bronze equestrian statue of Jackson in Washington.5 On September 10, O’Sullivan and Secretary of State James Buchanan met with President James K. Polk, asking him to join the committee to raise funds for the Jackson statue. Polk declined but volunteered to head the subscription list. Called “Young Hickory,” he had been a protégé of Jackson, who, as head of the Democratic Party, had selected Polk as the Democratic candidate for president in 1844.

Later in September 1845, the Jackson Monument Committee was established at a meeting at Apollo Hall in Washington to raise the funds to erect an equestrian statue. The statue was to emphasize Jackson’s military rather than political career. Members of the committee included John Peter Van Ness, a former congressman from New York and former mayor of Washington City; James Hoban Jr., son of the architect of the White House; Cave Johnson, postmaster general under President Polk; and Benjamin B. French, commissioner of public buildings and a prominent Mason in Washington.6

Various people helped in planning the statue. Jeremiah G. Harris, editor of the Nashville Union, wrote to American sculptor Hiram Powers in Italy in 1846 to inquire about the cost of a bronze equestrian statue. Powers replied that the total cost would be approximately $30,000, including the cost of casting, which he estimated to be half of that amount. Powers tried to get the commission for the Jackson statue through his occasional agent, Miner Kilbourne Kellogg, an artist from Cincinnati and man of the world. Kellogg had painted a portrait of Andrew Jackson and was at the time managing for Powers the American tour of his Greek Slave, the demure nude that made Powers a household name. Kellogg informed the committee that Powers did not need to submit a model because his work was famous.7 In April 1847 the committee asked Robert Mills, the Washington, D.C., architect who had designed several important public buildings in the city, to submit a plan. Mills’s design consisted of a 130-foot-tall triumphal arch that was to be climaxed by a statue by Powers of a standing Andrew Jackson, on its roof. This plan was rejected because of its prohibitive cost.8

Quite by chance, committee member Cave Johnson met the sculptor Clark Mills at a Washington dinner. Mills was entirely self-taught but already recognized for his talents. After being orphaned in Onondaga County, New York, at the age of five, Mills had lived with a maternal uncle, who was cruel to him. At age 13, he ran away and worked on a farm. Several years later he settled in Charleston, South Carolina, where he learned the art of plaster modeling. In 1835 he developed a new and advanced method of making life masks. He progressed to sculpting busts, first in plaster and then in marble. His marble bust of native son John C. Calhoun in 1844 won him immediate recognition and a gold medal from the mayor and city council of Charleston.9 In 1847 a group of three wealthy Charlestonians offered to pay Mills’s way to study sculpture in Italy. Before Mills left for Europe, Senator William C. Preston of Columbia, South Carolina, paid his expenses to travel to Richmond and Washington to study public sculpture there. In the State Capitol in Richmond, Mills was inspired by the portrait statue of George Washington by Antoine Houdon, which had been modeled from life in 1792. In Washington, he was greatly impressed by the fourteen neoclassical sculptures that he saw at the U.S. Capitol.10

Self-taught sculptor Clark Mills was commissioned by the Jackson Monument Committee to create the Jackson equestrian statue in 1848. He made his casting in a temporary foundry on the Ellipse. He also cast here an equestrian statue of George Washington that stands at Washington Circle on Pennsylvania Avenue. At a later octagon-shaped foundry he built on Bladensburg Road he cast Thomas Crawford’s Freedom, which was placed atop the dome of the Capitol in 1863.

Library of CongressAfter Johnson suggested to Mills that he submit a model of an equestrian statue of Jackson to the Jackson Monument Committee for consideration, Mills gave up his trip to Europe to work full time on the Jackson statue. In preparation, he studied the anatomy of various breeds of horses and even dissected some. From reading biographies of Jackson, he learned that the name of Jackson’s horse at the battle of New Orleans was Duke.11 After working on the model for eight months, Mills received a commission from the committee in March 1848. He accepted $12,000, which had been raised for the work by the committee.

Many were skeptical of the committee’s choice, since Mills had never even seen an equestrian statue, much less cast one. To concentrate on his work, he left his wife and four young sons at home in Charleston—for five years—and built a wooden structure near the south end of the Treasury Department Building, at Fifteenth Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, to serve as his foundry and residence. Mills used his Thoroughbred horse, Olympus, as a model, and he trained it to rear on its two hind legs in his studio. By December 1848, Mills had completed the full-size plaster model of the horse.12

For accuracy, Mills borrowed General Jackson’s uniform, saddle, and bridle from the Patent Office, where they were kept as relics. He read a number of books on casting bronze and experimented in order to learn the process. For practice, he cast two bronze bells in his studio in June 1850. The government then gave Mills a number of old weapons to melt down to obtain bronze for the Jackson sculpture. The four cannons Jackson had captured from the Spanish in his Pensacola Campaign in 1818 were considered historic trophies and reserved for placement around the base of the statue. By August 1851, Mills had completed casting the figure of Jackson, but not the horse. There had been setbacks. The crane to lift the statue failed; the furnace burst. But by January 1852, Mills had completed the castings: the horse was cast in four parts and the Jackson statue in six parts. The total weight of the sculpture was 15 tons.13

Self-taught sculptor Clark Mills was commissioned by the Jackson Monument Committee to create the Jackson equestrian statue in 1848. He made his casting in a temporary foundry on the Ellipse. He also cast here an equestrian statue of George Washington that stands at Washington Circle on Pennsylvania Avenue. At a later octagon-shaped foundry he built on Bladensburg Road he cast Thomas Crawford’s Freedom, which was placed atop the dome of the Capitol in 1863.

James Goode Collection, Library of CongressAmid great fanfare, the statue of Andrew Jackson was dedicated in Lafayette Park on January 8, 1853, the thirty-eighth anniversary of the battle of New Orleans. An elaborate parade preceded the dedication. A distinguished group including General Winfield Scott, Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, and the mayor and city council of Washington marched to the entrance of the White House, where they were greeted by President Millard Fillmore and his cabinet. Through a crowd of more than twenty thousand, they marched across the street to Lafayette Park for the dedication. Senator Douglas gave an address on the military accomplishments of General Andrew Jackson and then introduced Clark Mills. Mills was so overcome with emotion that he could not speak and only pointed to the statue, which was then unveiled amid cheers and the salute of General Scott’s artillery.14

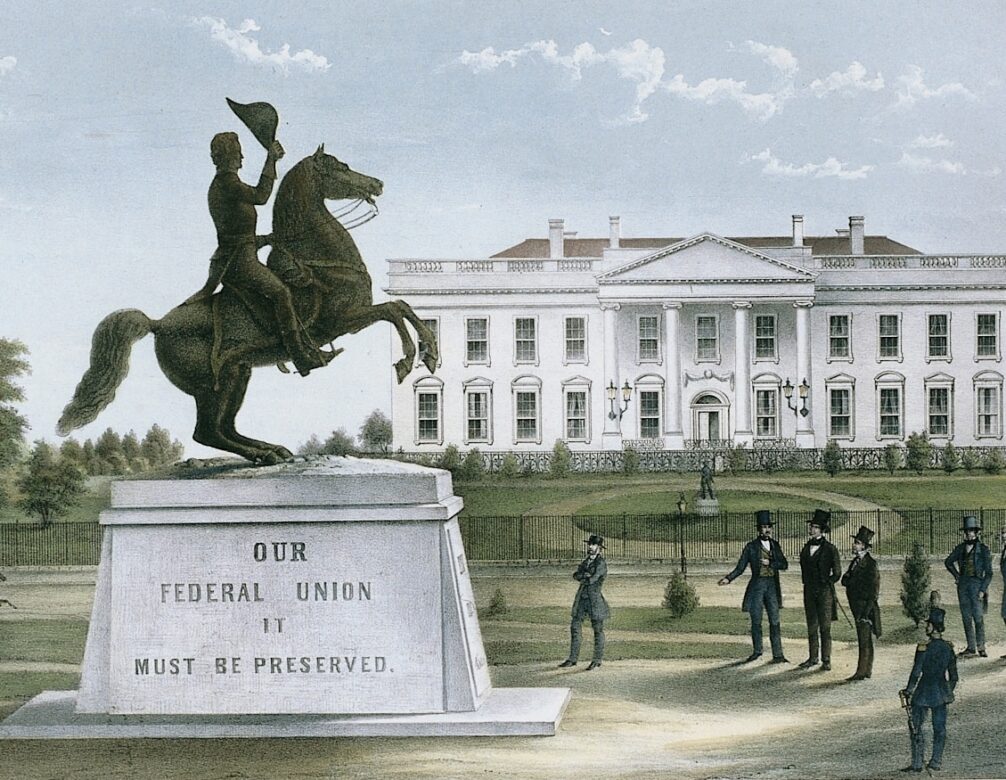

The inscription on the west side of the marble pedestal reads “Jackson” and “Our Federal Union It Must Be Preserved,” Jackson’s toast at a banquet celebrating Thomas Jefferson’s birthday on April 13, 1830. The phrase related to the nullification crisis, in which South Carolina had threatened to secede.15 Shortly after the dedication of the statue, the four Spanish cannons were placed at the corners. The pair on the north had been cast at the royal foundry in Barcelona in 1748 and were named for two Visigoth kings: El Witiza and El Egica. The two on the south were cast in 1773 and were named for two Greek gods: El Apolo and El Aristeo. The statue and cannons were enclosed by an iron fence soon after the dedication.16

To celebrate the dedication, a number of 2 foot high models of the Jackson statue were cast in 1855 at the Cornelius & Baker foundry in Philadelphia. Several copies survive today, including examples at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, the Treasury Department Building in Washington, D.C., the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore, the Hall of History in Raleigh, North Carolina, and the Historic New Orleans Collection. Congress not only paid $8,000 for the pedestal for the Jackson statue but appropriated $20,000 for a direct payment to Clark Mills because the original $12,000 that he was given by the Monument Committee covered only the cost of the casting. The federal government then claimed ownership of the work.17

After the Mills statue was erected in Lafayette Park in 1853, other realistic American equestrian statues quickly followed in the same decade, including that of George Washington by Thomas Crawford for the Virginia Capitol grounds in Richmond and another of George Washington by Henry Kirke Brown in Union Square in New York.18

A view of the Jackson equestrian statue from the north looking toward the White House. A hand-colored lithograph published in 1853 and entitled “Mills’s Colossal Equestrian Statue of General Jackson,” shows the inscription on the north side that was not actually placed on the west side until 1909.

Albert H. Small CollectionLafayette Park, where the statue was erected, was originally part of the larger President’s Park when the White House was first occupied by President John Adams in 1800. It was named in 1824 when the Marquis de Lafayette visited Washington, D.C., on his triumphant tour of the United States. Between 1891 and 1910, four monumental sculptured memorials to foreign generals who served in the Continental Army under General George Washington were placed in the corners of Lafayette Park: Lafayette, the Comte de Rochambeau, Friedrich Wilhelm, Baron von Steuben, and Tadcusz Kosciuszko. The first one, the Lafayette Monument, was scheduled to be situated along Pennsylvania Avenue due south of the Andrew Jackson statue, where it would have blocked the view of Jackson from the White House. Although the foundation had already been laid, Senator William B. Bate of Tennessee had an act passed in August 1890 to move it to the southeast corner of the park so as not to block the view of Jackson.19

Between 1920 and 1940 many other Washington residents tried to convince the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts to switch the Jackson statue with Mills’s roughly contemporary equestrian statue of George Washington at Washington Circle. But Charles Moore, secretary of the commission, insisted that the Jackson statue should remain in place for historical reasons. He also felt that the Jackson statue had a certain charming naive quality that the awkward statue of Washington lacked. The commission also blocked an attempt in 1917 by Postmaster General A. S. Burleson to move the Jackson statue in front of the Treasury Department Building. In 1914 landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. wanted to turn the Jackson statue around to face Sixteenth Street. In 1934 Charles Moore again blocked an effort by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to have the statue exchanged with Mills’s Washington.20

Originally, the Navy Urns, copies of the Medici Urn in Florence, Italy, were placed in Lafayette Park to mark the east and west entrances. In 1970, they were moved to their present location on the south side of the park framing the Jackson statue. The other main change to the park’s setting for the statue took place in the late 1930s, when the original 1851 site plan by landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing was simplified by removing a number of the minor footpaths.21

The earliest known photograph of the Jackson equestrian statue is dated c. 1855. It is in the collection of Saint John’s Episcopal Church, which can be seen beyond the park on H Street.

Saint John's Episcopal Church Collection

A view of the Jackson equestrian statue from the north looking toward the White House. Photographer Bruce White captured the view on a spring day in 2008.

White House Historical Association

A recent photograph of the Jackson equestrian statue in Lafayette Park. In order to depict the details of his subject correctly, sculptor Clark Mills studied the anatomy of horses and borrowed General Jackson’s uniform, saddle, and bridle from the Patent Office, where they were kept as relics. In the foreground of the photograph is one of the pair of bronze copies of Florence, Italy's Medici Urn, cast in Washington in 1872 at the request of W. W. Corcoran, to show the outstanding capabilities of the Navy Yard Foundry.

White House Historical Association

A recent photograph of the Jackson equestrian statue in Lafayette Park. In order to depict the details of his subject correctly, sculptor Clark Mills studied the anatomy of horses and borrowed General Jackson’s uniform, saddle, and bridle from the Patent Office, where they were kept as relics.

White House Historical AssociationWhen leading citizens in New Orleans learned of the equestrian statue being made by Mills for Washington, D.C., they ordered a replica for their city, the site of Jackson’s great military triumph. In January 1851, they formed the Jackson Monument Association in New Orleans and successfully petitioned the mayor and city council to locate the statue in the Place d’Armes, the city’s central square, which would be renamed Jackson Square. The change marked the decline of Creole New Orleans and the ascendancy of the Americanized city.

The Place d’Armes had been laid out in 1722 by Adrien de Pauger, a French engineer, as a place to drill the militia. Nearly a century later, on January 23, 1815, General Jackson and his staff walked amid a crowd of well-wishers through the square and under a triumphal arch to enter the Saint Louis Cathedral, where he gave thanks for winning the battle of New Orleans. By the time the Jackson statue was erected, the barren square was completely landscaped with circular paths, fountains, trees, flower beds, new gas lamps, and an iron fence. Benches and statues of the four seasons were placed in the corners.22 This square, with its antebellum buildings on three sides, was then and still is the most beautiful site in New Orleans.23 The Jackson statue is fronted on two sides by the Upper Pontalba Building and the Lower Pontalba Building of 1849–51, the first apartment buildings built in the United States. A third side overlooks the Mississippi River, while the fourth faces Saint Louis Cathedral, which is flanked by the Cabildo and the Presbytere. By the 1850s, these two early Spanish structures were used by the state supreme court and by the city as a courthouse. Today they constitute the Louisiana State Museum.24

After the association had difficulty in raising the $35,000 needed for the sculpture, the Louisiana legislature in 1852 appropriated $20,000 to help fund the project. One of the principal donors was Baroness Micaela Pontalba, the builder of the Pontalba Buildings, who sent $1,500 from France.25 With the funds raised, Mills signed a contract to cast a second bronze equestrian statue of Jackson for the city in August 1853, agreeing to have it completed and delivered by 1856.26 Along with the appropriation for the Jackson statue in 1852, the legislature also gave funds for the construction of a 150 foot tall marble obelisk across the river on Chalmette plantation, the site of the battle of New Orleans.27 A well-known New Orleans stonemason, Newton Richards, was selected to design and build the Chalmette battlefield monument as well as a granite pedestal for the Jackson statue.28

Engraving of Jackson Square, c. 1860.

The Historic New Orleans CollectionThe dedication of the New Orleans Jackson statue was scheduled for January 8, 1856, but was postponed until February 9 because the ship bringing it from Baltimore, The Southerner, was delayed en route by bad weather.29 To prepare for the statue, workmen had to dig up the foundation with a cornerstone that had been laid near the center of the square in 1840 for a future statue of Jackson and place it under the new pedestal.30 As part of the dedication celebration, there was a long parade with militia units, bands, and dozens of artisan groups including the packers of cotton bales on the New Orleans wharves.31 Among the many veterans who marched were a number of men who had fought under Jackson at the battle of New Orleans. One who was honored during the ceremonies had raised the U.S. flag in what later became Jackson Square when the Louisiana Purchase took effect in 1803.32

During the Civil War and Reconstruction, New Orleans was occupied by Union troops for fifteen years, longer than any city in the United States, from 1862, when it was captured by Admiral David Farragut, until President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew federal troops in 1877. Between April and December 1862, General Benjamin Butler, with 18,000 U.S. troops, occupied the city.33 Butler arrested the mayor, removed the city council members from their positions, placed the city under martial law, and seized property of those who refused to take the oath of allegiance. In a final act to insult the citizens of New Orleans, Butler ordered a stone carver to incise the following inscription on the side of the pedestal of the Jackson statue: “The Federal Union, It Must and Shall Be Preserved.”34

A ribbon from the dedication of the Jackson statue dated February 9, 1856.

The Historic New Orleans CollectionAt the time of Jackson’s death in 1845, a number of Nashville citizens recommended that a statue of him be erected in the city that was so close to The Hermitage.35 In February 1846, the Tennessee legislature appropriated for this purpose $7,500, the remainder to be paid by private funds.36 Nothing came of this effort, due to the high construction cost of the new Tennessee State Capitol designed and supervised by William Strickland between 1845 and 1859, followed by the upheaval of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

By 1874, the Tennessee Historical Society was reorganized and revitalized by new officers. Its board decided in 1878 to make an all-out effort to celebrate Nashville’s centennial in 1880. In July 1879, the board voted to buy a copy of Mills’s equestrian statue of Jackson for the Capitol grounds in Nashville. Colonel John Bullock of Nashville negotiated with Mills for the purchase of the statue and was successful in reducing the price from $12,000 to $5,000.37

In response to the board’s petition for help in celebrating the city’s centennial, the mayor established an official Nashville Centennial Commission, composed of businessmen as well as officers of the Tennessee Historical Society.38 It was a union of those who wanted to display historic relics and proclaim the state’s history with younger leaders who wanted to advertise the capital city as an industrial and commercial center of the New South.

A recent photograph of the Jackson statue with Saint Louis Cathedral in the background.

Infrogmation of New OrleansThe celebration of Nashville’s centennial consisted of four elements. The first was the purchase of the Jackson statue by the Tennessee Historical Society. The others, organized by the Centennial Commission, were a major parade, a program of lectures on the history of Tennessee, and the construction of a large temporary exhibition hall. This last was built in 1880 at the corner of Eighth Avenue and Broadway and modeled on the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries Building, then under construction on the Mall in Washington, with two stories, symmetrical corner pavilions, and a low dome. Personal items of Andrew Jackson were borrowed from his family at The Hermitage and put on display together with the latest products manufactured in Nashville.39 The board of the Tennessee Historical Society also voted on July 1, 1879, to purchase The Hermitage from the Tennessee legislature in order to open it to the public as a house museum. The legislature had purchased the plantation from Andrew Jackson Jr. in 1857, when he was experiencing financial difficulties, but allowed the family to remain in residence at no cost.40

The Nashville statue was installed on the east plaza of the Tennessee State Capitol, which was added to the grounds in the 1870s.41 At the dedication on May 20 a round of speeches extolled Jackson’s character and military expertise, and then the sculptor Clark Mills made a brief address. At a signal given by Enoch H. Smith, a veteran of the battle of New Orleans, the statue was unveiled.42 By a curious arrangement, it had been covered with two bowed, canvas-covered wooden frames, which concealed a half dozen militia men. At the signal, they pushed the two frames open, as a clam shell opens, revealing the statue to great applause.43 The statue rested on a temporary wooden pedestal made of logs shielded by boards on the outside. It was replaced by a permanent limestone pedestal in 1884.44

The unveiling of the Jackson equestrian statue at the Tennessee State Capitol Building in 1880.

Tennessee State Library and ArchivesThe most recent of the four equestrian statues of General Andrew Jackson was erected in 1987 in downtown Jacksonville, Florida, at the Jacksonville Landing, located at the corner of Hogan Street and Independent Drive. Democratic Congressman Charles Bennett began raising funds for the sculpture in 1985. Within a year he had more than $100,000 for the work and proceeded to seek bids for the casting. Robert Springer of the Modern Arts Foundry in Long Island City, New York, won the bid. The National Park Service worked with Springer to get the exact dimensions of the statue in Lafayette Park.45 When completed, the statue was erected on a circular grassy knoll 100 feet from the north bank of Saint Johns River. The inscription on the front reads “Andrew Jackson / After Whom Jacksonville Was Named / 1822” and on the rear “Andrew Jackson / First Governor of Florida Under the United States Flag—1821.” The marble pedestal was designed by the Jacksonville architect Ted Pappas.46 At the dedication ceremony Bennett said that Jackson was probably the person most responsible for making Florida suitable for settlement because of his efforts in fighting the Spanish and the Indians.47

Jackson was, in fact, closely identified with the early development of Florida. In the early 1800s, when Florida was owned by Spain, local Seminole Indians began raiding American settlements in Georgia and Alabama, and in 1818 General Jackson was sent to Florida to quell these attacks. At the time, Florida was split into two jurisdictions: East Florida with its capital at Saint Augustine and West Florida, its capital at Pensacola, its territory extending west to the Mississippi River. After defeating the Seminoles, a branch of the Creeks, in the First Seminole War, Jackson occupied Pensacola. In the subsequent negotiations with Spain, the United States acquired Florida, agreeing to assume $5 million in claims by U.S. citizens against Spain. In 1821, Jackson was appointed military governor of Florida, and the next year the new town of Jacksonville was named in his honor.

The equestrian statues of General Andrew Jackson are impressive reminders of the cultural history of the American cities in which they stand. They commemorate the battle of New Orleans, one of the most celebrated victories in the history of the country, and the man himself. The statue itself is distinctive as the first bronze sculpture cast in the United States. It is also remarkable that the self-trained sculptor, Clark Mills, created the first equestrian statue in the world in which the rider and horse are perfectly balanced on the horse’s rear legs. His achievement is testimony to American inventiveness and resourcefulness, applauded both in America and in Europe.

The Jackson equestrian statue on the Capitol grounds in 1880.

Tennessee State Library and Archives

Jacksonville’s dramatic modern skyline looms over the 1987 casting of Mills’s equestrian Jackson, for whom the north Florida city is named.

The Florida Times-Union, John PembertonFrom First Lady Dolley Madison's sister Lucy Payne Washington's wedding in 1812 to the nuptials of President Joseph Biden and First...

Over 200 years ago, James Hoban left Ireland for America to pursue his dream of becoming an architect. Selected by President...

Every year since 1981, the White House Historical Association has had the privilege of designing the Official White House Christmas Ornament....

Since 1965, the White House Historical Association has been proud to fund the official portraits of our presidents and first ladies,...

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr., the nation’s only unelected president and vice president, served thirteen terms in Congress before rising to...

From hot dogs to haute cuisine, U.S. Presidents have communicated important messages through food. Stewart McLaurin, President of the...

In 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was sworn in for the first of his four terms as president of the United States....

The American experiment has long held the curiosity of people around the world, especially for Iain Dale, an award-winning British...

Thousands of people traverse historic Lafayette Park every day to get a glimpse of the White House. The park, right...

Honoring some of the greatest moments in sports history has become a tradition at the White House. Presidents and their...

Since the laying of the cornerstone in 1792, Freemasons have played an important role in the construction and the history of...

Every year since 1981, the White House Historical Association has had the privilege of designing the Official White House Christmas Ornament....