Collection The Decatur House Slave Quarters

In 1821-1822, Susan Decatur requested the construction of a service wing. The first floor featured a large kitchen, dining room,...

Main Content

Slavery and Art in the White House Collection

How Long? 8 minutes

This article is part of the Slavery in the President’s Neighborhood initiative. Explore the Timeline

Charles Willson Peale is synonymous with eighteenth-century portraiture. His depictions of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and other famous Americans are displayed in several of the country’s most prominent art galleries and museums, including the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the White House. In his lifetime, Peale fostered close relationships with U.S. presidents, opened the first American museum, and left an indelible mark on Revolutionary era art. However, Peale’s fame and talent have long obscured a significant part of his life: his slave ownership.

Fine arts and taxidermy animals are visible behind the curtain of Peale's museum in this 1822 painting. Moses Williams worked at the museum, creating silhouettes of guests.

Library of CongressCharles Willson Peale was born to parents Margaret and Charles Peale in 1741 and was raised on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.1 Before pursuing art as a vocation, Peale trained with a saddle-maker in Annapolis and in 1762, he married his childhood sweetheart, Rachel Brewer.2 Soon after, Peale began his artistic career and studied painting in America and Britain. During these travels, he met artists including John Singleton Copley in Boston and Benjamin West in London and greatly improved his craft under their tutelage.3

Upon returning to America, Peale’s career as a portraitist prospered. Like many prominent Americans of the period, he signified his family’s status by purchasing an enslaved couple named Lucy and Scarborough; unfortunately, the details and circumstances surrounding these transactions are unclear.4 Charles Coleman Sellers, historian and great-grandson of Peale, speculated that “they may have been given to him in exchange for portrait work by some planter.”5

In 1775, Peale, his family, and their enslaved servants moved from Maryland to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he became an active participant in and artist of the American Revolution. During the war, Peale served in the Pennsylvania militia and fought at the Battles of Trenton and Princeton.6 During this period, he also earned portrait commissions from a number of Revolutionary leaders, including Thomas Jefferson and George Washington. Both men became frequent sitters and correspondents of Peale’s. Learn more about the enslaved households of President Thomas Jefferson and President George Washington.

Peale's portrait, George Washington at Princeton, 1779. He went on to paint Washington many times.

U.S. Senate CollectionDuring the 1770s and 1780s, Peale’s family expanded, and in his lifetime, he would father seventeen children and marry three times.7 In fact, he ensured his artistic legacy by naming a number of his children after celebrated artists—including Raphaelle, Rembrandt, Titian, and Rubens. Many followed their father into the world of art and paintings by Rubens and Rembrandt Peale are part of the White House Collection today.

Peale’s enslaved servants Lucy and Scarborough also expanded their family in the Revolutionary era— their son, Moses Williams, was born into slavery in the 1770s.8 According to Peale’s son, Rembrandt:

My father, coming from Maryland to the Quaker City, brought with him a family of slaves, whom he shortly after manumitted, except Moses, the eldest boy, who being too lazy to work, my father was compelled to keep in bondage, with the promise or rather threat that as soon as he should show himself capable of self-maintenance, he should be free; but capable or not, at eight and twenty he should give him his discharge...9

Details of Lucy and Scarborough’s manumission are the subject of speculation among historians, though many cite 1786 as the year they obtained freedom.10 This excerpt by Rembrandt Peale which calls Moses “too lazy to work,” may also illuminate an act of deliberate resistance to bondage by Moses.11 Peale also “hired out” enslaved workers owned by others when he desired additional laborers.12

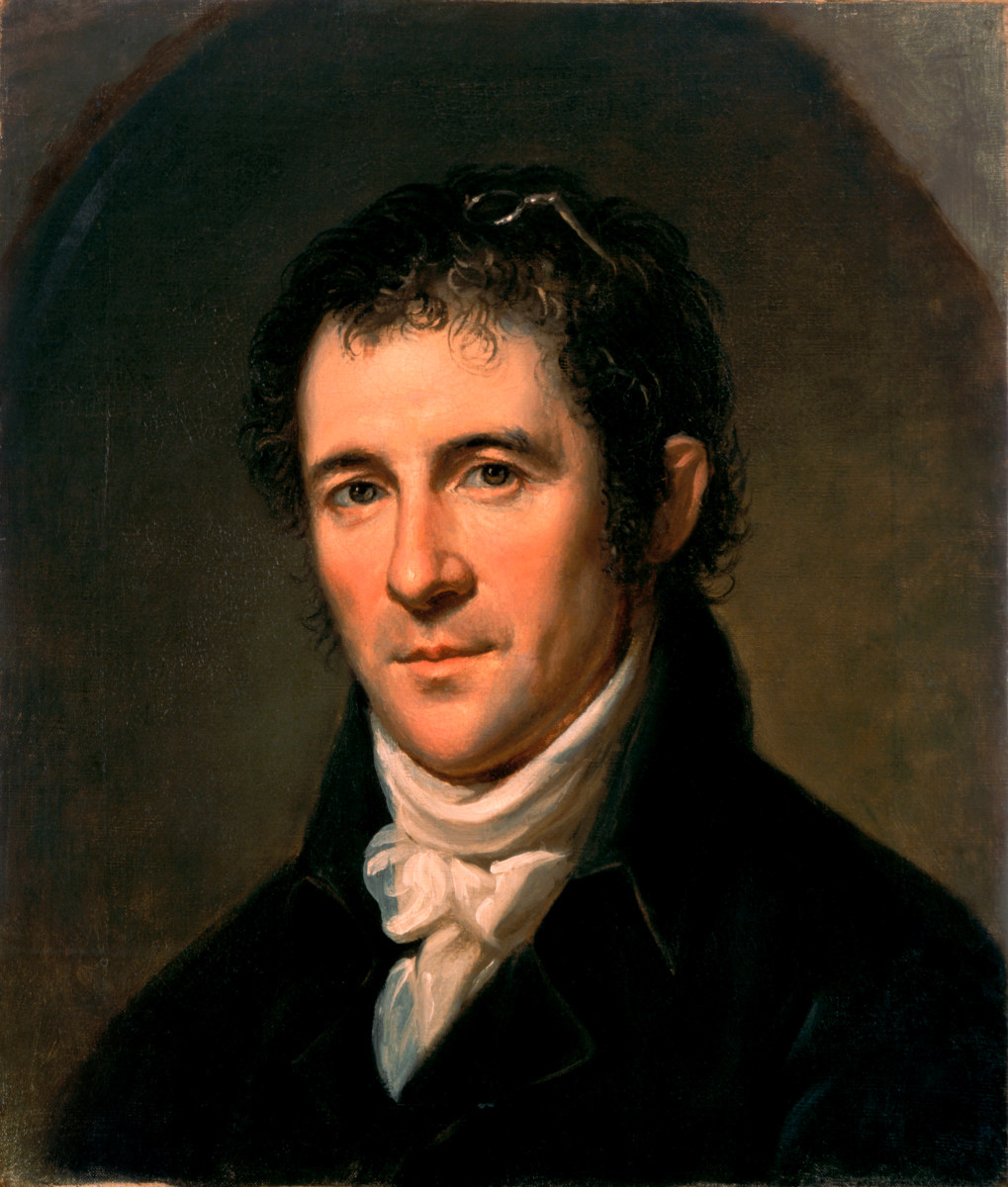

Charles Willson Peale, 1807

Library of CongressLike many of his contemporaries, Peale’s relationship with slavery was complicated. Although he enslaved multiple people, many of his peers considered him an abolitionist—especially after he voted in favor of Pennsylvania’s Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery while serving in the state assembly in 1780.13 Though the act did not abolish slavery outright, it limited its scope and weakened the power of slave owners in Pennsylvania; for example, children born into slavery in Pennsylvania were considered “indentured” rather than enslaved and had to be emancipated by their twenty-eighth birthday, and any enslaved person residing in Pennsylvania for more than six consecutive months was declared free.14 Notably, President George Washington rotated his enslaved servants at the President’s House in Philadelphia in order to avoid this provision, sending them back to Mount Vernon.15

Indeed, Peale’s discomfort with human bondage is evident in his personal papers while discussing a visit to Washington’s estate in 1804. Though Washington had died about five years earlier, Peale stopped at Mount Vernon and stated: “It is surely a miserable situation to be surrounded with a number of Slaves, however kindly they may be used, yet the very Idea of Slavery is horrible.”16

Peale also depicted well-known abolitionists through his artwork, including John Laurens, the Marquis de Lafayette, and free and enslaved Black Americans. In 1819, for example, he painted a free Black man named Yarrow Mamout. Peale heard rumors that Mamout was 140 years old, sparking his interest.17 Though this rumor was false, Mamout had led a fascinating life. Born in Guinea, slave traders captured Yarrow Mamout as a child and forcibly brought him to the United States via the Middle Passage.18 Traders sold Mamout into slavery in Maryland; he later lived in bondage in Georgetown until his manumission in 1796.19 Yarrow went on to become a successful businessman in the neighborhood, owning stocks, purchasing a home, and buying his son’s freedom. Typically, sitters paid the artist for their portraits, but Peale paid Mamout to sit for him, and he painted him in a good-humored, dignified manner comparable to portraits of white subjects.20

Yarrow Mamout, painted by Peale in 1819, was a successful freedman in Georgetown.

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Purchased with the gifts (by exchange) of R. Wistar Harvey, Mrs. T. Charlton Henry, Mr. and Mrs. J. Stogdell Stokes, Elise Robinson Paumgarten from the Sallie Crozer Hilprecht Collection, Lucie Washington Mitcheson in memory of Robert Stockton Johnson Mitcheson for the Robert Stockton Johnson Mitcheson Collection, R. Nelson Buckley, the estate of Rictavia Schiff, and the McNeil Acquisition Fund for American Art and Material Culture, 2011Despite his support of antislavery legislation and expressed distaste for human bondage, Peale was a slave owner for many years. Though Peale had freed Lucy and Scarborough, their son Moses remained an enslaved apprentice until his manumission at the turn of the nineteenth century, at twenty-seven years old.21 While enslaved, he learned “taxidermy, animal husbandry, [and] object display” from his owner. Indeed, Williams earned his own freedom one year early, thanks to his talent as a silhouette-maker—a skill which he learned from Peale.

In the 1790s, Charles Willson Peale embarked upon a new professional journey: the creation of a museum in Philadelphia. It was the first of its kind in America, exhibiting "collections of art, science, nature and technology” for the general public.22 The museum also reinforced racial hierarchies of the early nineteenth century by exhibiting wax figures of different races and ethnicities and displaying indigenous remains for white Philadelphia audiences.23 Peale’s children were actively involved with the museum, as well as Moses Williams, who rose in prominence using an unusual device: the physiognotrace. This silhouette machine was installed in Peale’s museum in 1802, allowing for rapid, affordable likenesses of sitters. During the process, the subject “pressed his cheek against a concave wooden plate while a long brass gnomon was run lightly around his head.”24 The image was then traced onto paper, creating four silhouettes of the subject.25 According to Rembrandt Peale:

It is a curious fact, that until the age of 27, Moses was entirely worthless: but on the invention of the Physiognotrace, he took a fancy to amuse himself in cutting out the rejected profiles made by the machine, and soon acquired such dexterity and accuracy, that the machine was confided to his custody, with the privilege of retaining the fee for drawing and cutting. This soon became so profitable, that my father insisted upon giving him his freedom one year in advance.26

Thus, Moses Williams developed and leveraged his talent to become a free man, despite being called “worthless” by Rembrandt Peale. An accomplished cutter of profiles, Moses remained in the employ of Peale and later started a family in Philadelphia with the money he earned from his work. Very little is known about the rest of his life, though local news reports claimed that Williams may have taken up drinking and lost business as silhouettes declined in popularity.27 Many of Williams’s silhouettes survive today and can be seen in museum collections including the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the University Art Gallery in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Silhouette of Moses Williams, labeled "Cutter of Profiles"

Collection of the University of Pittsburgh Art Gallery, Courtesy of the Library Company of PhiladelphiaSince Charles Willson Peale’s death in 1827, he has been celebrated as a talented portraitist and innovative museum curator. However, the success of Charles Willson Peale’s career as an artist and naturalist is inexorably tied to slave ownership, which should also be acknowledged as a part of his legacy. Though it appears that Peale’s attitude toward slavery changed throughout his life, he was an active participant in human bondage for much of his life, benefitting from the labor and artistry of Lucy, Scarborough, Moses, and other unnamed enslaved workers whom he “hired out” in Philadelphia. Moreover, he made a name for himself and a fortune for his family by painting other wealthy slave owners, including Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. These portraits, as well as those painted by his children, hang in the halls of the White House—but behind each stroke of the paintbrush is a more complicated history.

Thomas Jefferson, Rembrandt Peale, 1800

Pieces in the White House Collection by Charles Willson Peale and his sons.

White House Collection/White House Historical Association

George Washington, Charles Willson Peale, 1776

Pieces in the White House Collection by Charles Willson Peale and his sons.

White House Collection/White House Historical Association

Still Life with Fruit, Rubens Peale, ca. 1862

Pieces in the White House Collection by Charles Willson Peale and his sons.

White House Collection/White House Historical Association

Benjamin Henry Boneval Latrobe, Charles Willson Peale, ca. 1804

Pieces in the White House Collection by Charles Willson Peale and his sons.

White House Collection/White House Historical AssociationIn 1821-1822, Susan Decatur requested the construction of a service wing. The first floor featured a large kitchen, dining room,...

Built in 1818-1819, Decatur House was designed by the English architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe for Commodore Stephen Decatur and Susan...

James Buchanan is often regarded as one of the worst presidents in United States history.1 Many historians contend that Buchanan’s...

On February 11, 1829, members of Congress convened to certify votes for President and Vice President of the United States as Andrew...

Through research and analysis of written accounts, letters, newspapers, memoirs, census records, architecture, and oral histories, historians, museum professionals, and...

Without photographs, paintings, or other visual representations of the Decatur House Slave Quarters from the antebellum period, it is difficult...

President William Henry Harrison’s famously brief month-long tenure at the White House makes it difficult to research the inner wo...

In 1868, Elizabeth (Lizzy) Hobbs Keckly (also spelled Keckley) published her memoir Behind the Scenes or Thirty Years a Slave, and...

As we consider life in the President’s Neighborhood, the unusual story of the Wormley Hotel and its Black founder, Ja...

In 1818, John Gadsby was assessed and taxed for owning thirty-six enslaved individuals in Baltimore—including two young women named “Maria” and “K...

Often, the accomplishments and contributions of enslaved people are lost to history—undocumented, ignored, or forgotten by successive generations. One of...

In the late eighteenth century, the original thirteen colonies dissolved and formed the United States. In 1787, delegates to the Constitutional...