Podcast Abraham Lincoln, Robert Burns, and the Scottish Connection

There is a long history of Scottish influence on the White House, dating back to the Scottish stonemasons that contributed...

Main Content

How Long? 9 minutes

On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office and became the sixteenth President of the United States. While he had no way of knowing the extent challenges ahead, a pall hung over the celebrations as the nation hovered on the brink of civil war. To lead the nation during the looming crisis, Lincoln appointed a group of opinionated, stubborn, and powerful secretaries, which became known as his “team of rivals.” Captured beautifully by historian Doris Kearns Goodwin and then featured in the film Lincoln, Lincoln’s cabinet is one of the best known in American history.

President Lincoln carefully selected his department secretaries to bring diverse skills and perspectives into his cabinet. He recognized that cabinet appointments offered a valuable opportunity to build coalitions and strengthen tenuous bonds between factions remaining in the Union. First, Lincoln selected former Republican Party rivals for three of the most important cabinet positions: Senator William H. Seward of New York became the secretary of state, Governor Salmon P. Chase of Ohio became secretary of treasury, and Missouri’s elder statesman Edward Bates became the attorney general. These appointments also extended representation to crucial states from the northeast, old northwest, and border states. Next, Lincoln appointed former Democrats to build bipartisan support: Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. All six were more educated, better known, and had more government experience than Lincoln himself. They also brought gravitas to the new administration. While they initially resented Lincoln for his success, they grew to respect his political savvy. Bates even admitted that the president was “very near being a perfect man.”1

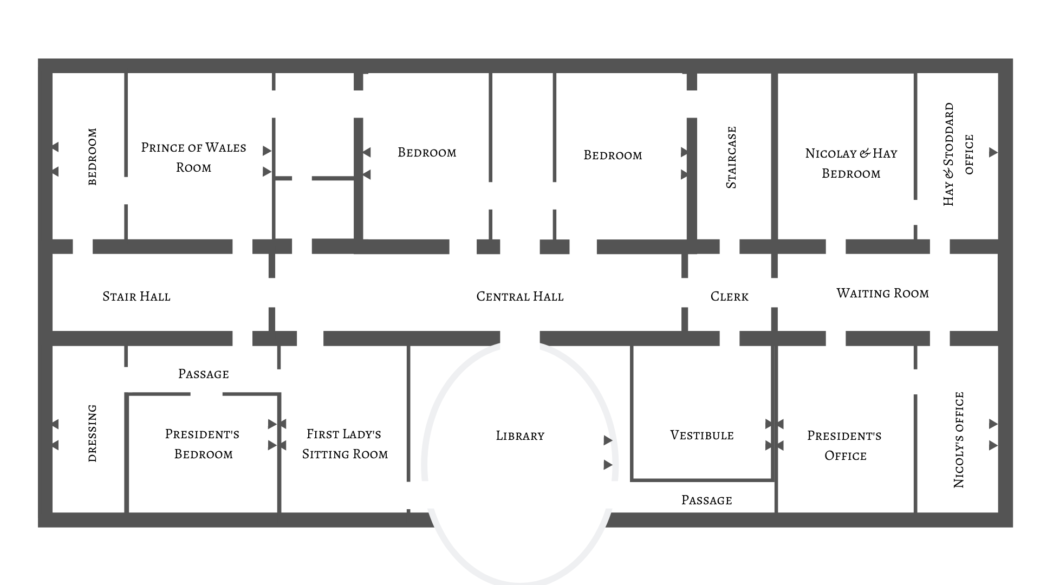

Floorplan of the second floor of the White House during Abraham Lincoln’s presidency.

Created by Dr. Lindsay M. Chervinsky, 2020.The secretaries were familiar faces at the White House. They visited several times a day to deliver news, discuss an issue with the president, or attend a meeting. They usually walked up the back stairs, through the waiting room at the center of the hall, and into Lincoln’s office. The eastern side of the Second Floor contained the executive work spaces. On the north side of the hall, Lincoln’s secretaries, John George Nicolay and John Hay shared a bedroom, and Hay shared an office with the third secretary, William Stoddard. On the south side, a vestibule and Nicolay’s office flanked the president’s office, which also served as the cabinet room.

The workspaces were worn and outfitted with tattered furniture. The waiting room had old-fashioned horsehair sofas and chairs for callers, dusty busts of former presidents, old prints of founding fathers, and a faded copy of the Declaration of Independence in a cheap frame. The carpet on the floor was a varnished oilcloth that was bare and soiled in spots around the spittoons.2 Both of the clerks’ offices had dark mahogany doors, marble mantels, and paneled wainscoting that harkened back to the 1830s. The floors had fraying carpets and dull green curtains that had been faded by the sun.

This photo depicts the stairs and doorway Lincoln used to access the family’s private rooms.

Library of CongressHay and Stoddard’s office offered a bit of a reprieve for Lincoln—a place where he could go relax for a few minutes, enjoy the company of his clerks, and take his mind off work. Bookcases with law books lined the walls, two upright desks stood in the corners, and wax figurines stood guard on the fireplace mantel. Stoddard spread out on a large table covered by an ink-stained green cloth. The legs of the table bore the distinct markings of Tad and Willie Lincoln’s handiwork after they received pocketknives as gifts and used the table to test the knives’ effectiveness. From his desk in the corner, Hay sat in his swivel chair and regaled visitors with stories. When he needed a break, Lincoln would recline in Andrew Jackson’s old leather chair and listen to his secretaries’ banter.3

Lincoln welcomed most guests in the president’s office, including the department secretaries. He referred to his office as “the shop” and this room was primarily a work space.4 The office featured old, hand-me-down furniture from former presidents, as Lincoln was not about to spend important government funds on an office renovation during the war. The most prominent feature was a long, wooden table in the middle of the room. This table was likely acquired sometime during the presidency of either John Quincy Adams or Andrew Jackson.5 A few maps and bundles of papers bound by rubber bands were usually spread across the table, pertaining to appointments, officer ranks, or troop movements. When the daily mail delivery arrived, the clerk poured out the contents of a large canvas sack on the table—often leaving thousands of letters for Nicolay, Hay, and Stoddard to sift through and sort.

This photograph of President Abraham Lincoln is by Anthony Berger, of photographer Mathew Brady's studio, and was taken on April 26, 1864. In the photograph, Lincoln stands tall in the Cabinet Room, which also served as President Lincoln's office. Lloyd Ostendorf is credited with retouching the image.

Collection of Lloyd OstendorfLincoln’s primary workspace was a mahogany upright desk that stood by the middle window. Some presidents, like Franklin D. Roosevelt, cover their workspaces with trinkets and gifts that symbolize important relationships or happy memories. Lincoln preferred little clutter or unnecessary things. His desk usually held additional bundles of papers and the most current or relevant maps with color-coded pins that he used to track Union generals and armies. Lincoln’s desk obscured a small doorway and staircase that opened into a private passage, which offered the president a path to the family’s quarters without interacting with the callers lingering in the waiting room.

The room was quite literally covered with maps, often obscuring the dark green and gold star wall paper. On the east side of the room, an old sofa leaned against the wall beneath a large spring roller with more maps. In the northwest corner, a standing rack held additional map rollers, and folios of maps were scattered across the floor, blanketing the dark green carpet with a buff diamond pattern.6

A few additional items remained from Lincoln’s predecessors. A bell rope dangled next to the fireplace to summon the staff, courtesy of James Buchanan. An old bust of Franklin Pierce loomed over the room and the brick arch underneath the mantel bore the marks of Jackson’s feet. A gas chandelier hung from the ceiling with a rubber hose that fed a lamp below, providing light for the table at night.7

This October 1864 ink and paper sketch by C. K. Stellwagen depicts President Abraham Lincoln's office on the Second Floor of the White House. Courtesy of Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, Ohio.

Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, OhioThe room’s best feature was the view. Outside the south-facing windows, visitors observed the Potomac River, General Robert E. Lee’s former house atop Arlington Heights, soldiers and cows milling about on the mall, and the unfinished stump of the Washington Monument.8

Much like the worn furnishings in the room, Lincoln frequently dressed in clothes that had seen better days. When in the office, Lincoln wore a black cravat and black broadcloth suit, which hung loosely on his tall, wiry frame. Sometimes he added a black or buff vest. His cuffs frequently wore out, which he rarely replaced, much to his wife’s dismay. On his feet, Lincoln wore blue socks, in need of darning, which showed when he kicked off his worn carpet slippers. If dignitaries showed up unexpectedly, Lincoln sometimes presented himself in a faded dressing gown, happy or perhaps unaware, of the surprise his appearance caused his guests.9

The meeting space and culture reveals much about Lincoln’s leadership. Lincoln never adopted particularly stuffy or formal manners, but he actually allowed few people into his inner circle. The cabinet secretaries were among the chosen and they had almost instantaneous access to Lincoln. They could stroll into his office at any time, a privilege that Seward exercised multiple times per day.10 Lincoln selected individuals he could trust, sought out their advice, and relied on their expertise. Although he reserved the final determination for himself, Lincoln’s secretaries were integral to his decision-making process.

This hand-colored wood engraving was published on April 6, 1861 during the early days of the Abraham Lincoln administration. The caption below the engraving describes a scene of office-seeking men gathered outside of the Cabinet Room waiting for a word with President Lincoln. The arched window and doorway of the East Sitting Hall, just outside of the Lincoln Bedroom, is depicted on the left.

White House Collection/ White House Historical AssociationUnlike Thomas Jefferson, Lincoln didn’t require the secretaries to come to the White House for meetings. Every morning, after eating a light breakfast, Lincoln walked across the street to the War Department to consult with Secretary Stanton and read the latest cables. He returned to the White House by ten o’clock to greet office-seekers and visitors. If First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln was in town, Lincoln used the private passage to avoid the constant crowds and return to the family quarters to enjoy lunch with his family. After dinner, he returned to the War Department at nine or ten o’clock for about an hour before retreating to the White House.11

Lincoln generally left the Treasury Department, attorney general, and State Department to function under the management of his secretaries. He didn’t know as much about financial matters and generally trusted Seward’s decades of experience to handle diplomacy. But from the very beginning, Lincoln treated the War Department as an extension of his own office and carefully monitored the war effort. He even consulted the other secretaries as a group when contemplating a major military decision.12 In the summers, the first family moved to Soldier’s Home to escape the summer heat in the White House, but each morning Lincoln would ride on horseback into town to work in his office and visit the War Department.13

This painting depicts a meeting in the White House in late 1862. On January 1, 1863, President Lincoln would sign the Emancipation Proclamation from the large wooden table seen in Waddell's depiction. In the painting, Lincoln meets with Livermore in his Cabinet Room and office, located on the Second Floor of the White House.

Peter Waddell for the White House Historical AssociationOfficial cabinet meetings took place twice a week in the president’s office, but when Lincoln required a meeting on unscheduled days, he sent a note to Steward or instructed Hay to dispatch messengers. Stoddard wrote that “these meetings are wonderfully secret affairs. Only a private secretary may enter the room to so much as bring in a paper. No breath of any “Cabinet secret” will ever transpire, so faithfully is the seal of this room guarded.”14

When the secretaries gathered, they were usually consumed with solemn matters, but the group also enjoyed each other’s company and often shared stories and laughter. Each cabinet secretary made themselves comfortable in their own way. Lincoln often paced or leaned against the mantel, while insisting his guests stay seated. The others stretched out on the sofa, propped their feet up on the table, or chomped on cigars.15 In these positions, the cabinet played a crucial role in most of Lincoln’s most notable moments as president, from the decision to surrender Fort Sumter and Pickens without a fight in 1861, to the Emancipation Proclamation, to the final campaign that led to Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.16

There is a long history of Scottish influence on the White House, dating back to the Scottish stonemasons that contributed...

White House Historical Association president Stewart McLaurin hosted a town hall featuring Jon Meacham at St. John’s Episcopal Church. Me...

Today, the celebration of Halloween conjures images of costumed trick-or-treaters, sweets, and jack-o'-lanterns; but there was a time when All...

Biographies & Portraits

From the beginning of its construction in 1792, until the 1902 renovation that shaped the modern identity and functions of the interior...

Thanksgiving is a relatively quiet and personal holiday at the White House, as it precedes a very busy season of...

Presidents have found different ways to escape the pressures and politics of the position. For early leaders, it was a...

In April 1789, George Washington took the oath of office in New York City. Constitutional guidelines for inaugurations are sparse, offering...

Baseball has been known as our national pastime and has links to the presidency as far back as the Abraham...

The origin of the "American Presidents" by Genevieve Ryan Bellaire is somewhat unique. One year, Genevieve's father asked her to...

The White House Collection and the Atlantic World Jennifer L. Anderson, Mahogany: The Costs of Luxury in Early America (Cambridge,...

AuthorsJAMES ARCHER ABBOTT is a graduate of Vassar College (B.A.) and the State University of New York’s Museum St...