Collection Native Americans and the White House

Native Americans hold a significant place in White House history. For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples, including the Nacotchtank and...

Main Content

How Long? 9 minutes

Lafayette Square, the neighborhood just north of the White House, has long been the site of protests, marches, memorials, and celebrations for LGBTQ+ activists.1 Throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, segments of the American public have demanded equal treatment in the workplace, in healthcare, and at home, regardless of sexual orientation. Inspired and often excluded by other social movements, including civil rights and women’s liberation, LGBTQ+ activists turned to public demonstrations and acts of civil disobedience in Lafayette Square to call for systemic change at the highest level of government.2

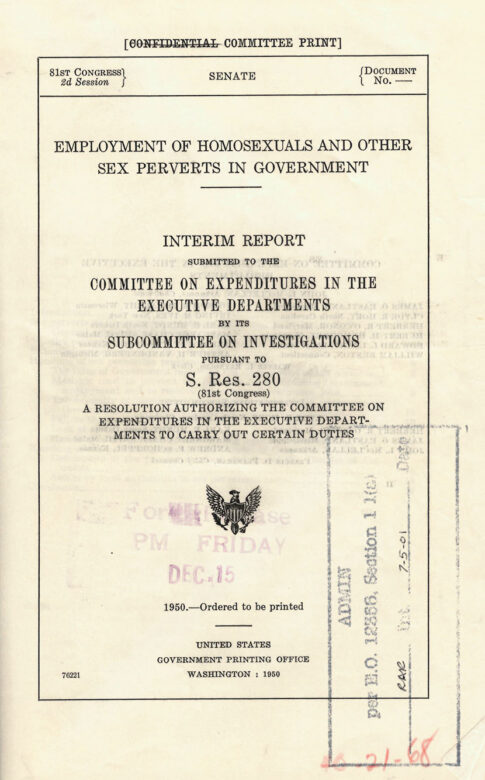

The “Lavender Scare” was the first motivation for public demonstrations related to LGBTQ+ rights at the White House. During the “Second Red Scare” of the Cold War, American politicians such as Senator Joseph McCarthy claimed that the U.S. government was infiltrated by communists, and in order to protect America these individuals needed to be investigated and removed from their positions. Many Americans today are familiar with the history of the Cold War and how American leaders and policymakers fought communism abroad, but less know of the deliberate efforts carried out by the federal government to prevent the spread of communism in the United States—including the surveillance and persecution of suspected “homosexual” citizens. Historically speaking, homosexuality was often purported as a form of deviancy or criminality. During the Cold War, it was frequently falsely linked to espionage and communism in an attempt to criminalize the behavior of LGBTQ+ citizens. This purge, also known as the “Lavender Scare,” began within federal agencies, who fired or forced the resignation of individuals suspected to be “homosexual.” The period between the late 1940s and the 1960s saw the dismissal of thousands of federal employees on these grounds.3 In 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower strengthened the legality of these dismissals when he issued Executive Order 10450, titled “Security Requirements for Government Employment.” The order expressly listed sexuality as a criterion for exclusion from federal service and emphasized the alleged security risk of employing LGBTQ+ Americans.4

The Hoey Report (1950) documented congressional investigative "findings" that falsely linked homosexuality to security risk in the federal workforce.

National Archives and Records AdministrationThe consistent deterioration of rights for LGBTQ+ citizens during the “Lavender Scare” led to the homophile movement and the first documented and organized gay rights picket at the White House on April 17, 1965.5 Frank Kameny, who had been fired from his job as a federal astronomer for being gay, led the demonstration alongside members of the Washington, D.C. chapter of the Mattachine Society, one of the oldest LGBTQ+ activist organizations in the country. Prominent lesbian activists Barbara Gittings and Ernestine Eckstein also picketed that day. Participants wore business attire to present themselves as respectable professionals and to draw attention to the issue at hand—discrimination in the workplace. Protest signs read: “Homosexual Citizens Want to Serve Their Country Too!” and “Sexual Preference is Irrelevant to Federal Employment!” The Mattachine Society later expanded these demonstrations to other important sites for federal employment in Washington, D.C., including the Pentagon.6 A few months later, they picketed the White House once again, and Kameny wrote to President Lyndon B. Johnson about their intentions:

A group of homosexual American citizens, and those supporting their cause, is picketing the White House, today, in lawful, dignified, and orderly protest—in the best American tradition—against the treatment being meted out to fifteen million homosexual American citizens by their government—treatment which constantly makes of them second-class citizens, at best.7

Like so many activist groups before them, these early protests by the Mattachine Society in Lafayette Square brought LGBTQ+ concerns before the eyes of the president—but the protests received little media coverage. Only one newspaper mentioned their April demonstration, theWashington Afro-American.8 Time and momentum soon spurred larger media attention, which bolstered the movement, expanded resources, and unified communities of LGBTQ+ activists and allies across the nation.

Protest sign from the Mattachine Society's 1965 White House protest

Collection of Frank Kameny, Smithsonian National Museum of American HistoryFour years later, the monumental Stonewall Uprising in New York City, led by prominent transgender activists including Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, brought crucial urgency, energy, and visibility to the movement for LGBTQ+ rights across America and laid the foundation for the gay liberation movement—more radical than the previous homophile movement. Following notable milestones for LGBTQ+ equality in the 1970s, including the election of openly gay politician Harvey Milk to government office and the American Psychiatric Association’s removal of homosexuality from their list of psychiatric disorders, the gay liberation movement became more vocal and celebratory than ever before. At the first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights on October 14, 1979, individuals reclaimed and celebrated their identities before the very government which refused to protect them. At least 25,000 protesters marched past the White House, gathering in Lafayette Square and on the National Mall to demand that the government:

During the 1980s, the HIV/AIDS crisis, which disproportionately killed gay men in the United States, led to a new wave of protests in Lafayette Square—particularly in response to President Ronald Reagan’s refusal to acknowledge the severity of the epidemic.10 The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), an activist organization dedicated to finding legislative and medical solutions to HIV/AIDS and ending the oppression of LGBTQ+ communities across America, became nationally recognized after leading a protest at the White House on October 11, 1987. ACT UP’s White House protest was part of the second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights and included demonstrations at the White House, Capitol Building, and Supreme Court. Nearly 200,000 participants called for funding and research for HIV/AIDS and protested against the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the illegality of sodomy in Georgia in the case Bowers v. Hardwick.11 The demonstrations culminated in the arrest of approximately 600 protesters who participated in acts of civil disobedience at the Supreme Court following the court’s decision—specifically, protesters were charged with “attempting to enter the Court for reasons other than official business.”12 These protests deliberately coincided with the first exhibition of the AIDS Memorial Quilt in Washington, D.C.—and both received robust media coverage.

The AIDS Quilt is a living memorial project that raises awareness for the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The personalized panels represent those who have died in the epidemic.

Library of CongressAfter the election of President George H.W. Bush, protests against government inaction regarding the HIV/AIDS crisis persisted. In 1992, ACT UP adopted a new method of protest, using the bodies of HIV/AIDS victims to illuminate the loss of life that accompanied presidential negligence in handling the epidemic. In a demonstration now called “Ashes Action,” protesters gathered in Lafayette Square and sprinkled the cremated ashes of partners, friends, and family members that had succumbed to HIV/AIDS through the White House gate and onto the president’s lawn.13 Eric Sawyer, an ACT UP organizer present at Ashes Action, recalled that “the police got their horses…and were trying to trample us,” and while “mounted U.S. Park Police pushed [protesters] back across E Street to the Mall,” no arrests were made.14 The powerful demonstration was considered such a media success that ashes were spread on the White House North Lawn again in 1996 during the Bill Clinton administration.15

ACT UP protesters, carrying the ashes of loved ones and friends, march toward the White House for “Ashes Action."

Photo by Saskia Scheffer/Lesbian Herstory ArchivesOther discriminatory federal regulations, including President Clinton’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy, prompted further LGBTQ+ rights protests in Lafayette Square that have stretched into the twenty-first century.16 In 2010, thirteen military service members and activists handcuffed themselves to the White House fence in front of Lafayette Park, calling for the repeal of DADT.17 U.S. Park Police forcibly removed the protesters and arrested them. In order to prevent similar protests in the future, the United States Secret Service (USSS) placed agents at intervals along the fence line. In 2014, USSS closed the sidewalk to the public after several individuals attempted to climb the fence and enter the White House.

The National March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation passes the White House in 1993.

Elvert Barnes PhotographyMeanwhile, political marches for LGBTQ+ rights have continued as a popular form of protest in and around Lafayette Square. The 1993 March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation remains one of the largest protests in American history, with approximately one million attendees; other large marches include the Millennium March (2000), the National Equality March (2009), and the National Pride March (2017).

Frank Kameny and President Barack Obama shake hands in the Oval Office after signing a Presidential Memorandum on Federal Benefits and Non-Discrimination, 2009.

National Archives and Records AdministrationThanks to its symbolic connection to the American presidency, Lafayette Park also serves as a site of celebration for milestones for the LGBTQ+ community. For example, after the Supreme Court’s decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, the White House celebrated marriage equality by illuminating the north façade with the colors of a rainbow. Happy couples gathered in Lafayette Square to celebrate the ruling. First Lady Michelle Obama snuck out of the White House with her daughter, Malia, to enjoy the celebrations. Obama wrote in her memoir:

The humid summer air hit our faces…And there it was, the hum of the public, people whooping and celebrating outside the iron gates. It had taken us ten minutes to get out of our home, but we’d done it. We were outside… with a beautiful, close-up view of the White House, lit up in pride.18

Celebrations outside of the White House, lit in rainbow colors, after the Supreme Court's decision in favor of marriage equality, 2015.

National Archives and Records AdministrationOn June 16, 2020, fifty-five years after the Mattachine Society’s White House protest, the Supreme Court ruled that LGBTQ+ citizens are protected from workplace discrimination under the Civil Rights Act of 1964.19 Still, many Americans experience unequal treatment based upon sexual orientation and gender identity both in public and in private. As a result, Lafayette Square simultaneously serves as a battleground for protesters in the past, present, and future, and a site of celebration for milestones among the LGBTQ+ community.

Special thanks to Saskia Scheffer and Hannah Byrne for their contributions to this article.

Native Americans hold a significant place in White House history. For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples, including the Nacotchtank and...

While there has yet to be a female president, women have played an integral role in shaping the White House...

The White House Historical Association and the Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project present this collaboration in an effort to open a...

For more than two centuries, the White House has been the home of American presidents. A powerful symbol of the...

For more than a century, thousands of Americans have gathered in Lafayette Park across from the White House to exercise...

First Lady Lou Hoover's invitation to Jessie L. DePriest to a White House tea party in 1929 created a storm of...

As part of the White House Historical Association’s 60th anniversary celebration in 2021, the Next-Gen Leaders (NGL) initiative was announced. Th...

A master of the art of practical politics, Lyndon Johnson came into the White House after the tragedy of President...

Before the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Building was built during 1922-25, a simple three-and-a-half story brick home stood in...

Five hundred and forty-seven dollars and fifty cents. According to the records of the District of Columbia that is the...

Every president since James Madison has attended services at St. John's Church. This distinctive yellow church was the second building...

The Rodgers HouseThe Rodgers House, formerly at 717 Madison Place, was constructed in 1831 by Commodore John Rodgers, a high-ranking naval officer....