The Households of James Buchanan

James Buchanan is often regarded as one of the worst presidents in United States history.1 Many historians contend that Buchanan’s...

Main Content

How Long? 9 minutes

This article is part of the Slavery in the President’s Neighborhood initiative. Explore the Timeline

“Would it be superstitious to presume, that the Sovereign Father of all nations, permitted the perpetration of this apparently execrable transaction, as a fiery, though salutary signal of his displeasure at the conduct of his Columbian children, in erecting and idolizing this… temple of freedom, and at the same time oppressing with the yoke of captivity and toilsome bondage, twelve or fifteen hundred thousand of their African brethren…making merchandize of their blood, and dragging their bodies with iron chains, even under its towering walls?” -Jesse Torrey, 1815

In 1815, abolitionist Jesse Torrey wrote these condemnatory words about the irony of American slavery and freedom while observing the ruins of the U.S. Capitol Building, burned by British troops during the War of 1812. Since its inception, the U.S. Capitol has symbolized democracy and liberty to the American public—but like the White House, enslaved laborers played a crucial and oft overlooked role in its construction, excluded from the very freedom it embodies.

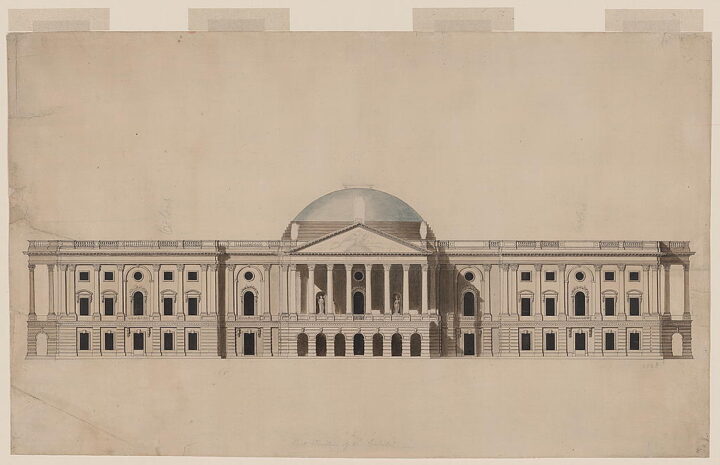

In 1790, the Residence Act officially established a new U.S. capital city along the banks of the Potomac River.1 President George Washington selected Frenchman Pierre “Peter” Charles L’Enfant to survey and plan the Federal City, better known as Washington, D.C. As part of this massive federal building project, L’Enfant oversaw the plans and early construction stages for two major structures: the President’s House and the U.S. Capitol. The federal government held a national competition to select the final design for the Capitol Building, judged by President George Washington, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, and Commissioners of the Federal District, Thomas Johnson, David Stuart, and Daniel Carroll.2 A design by Dr. William Thornton, featuring a central, domed section flanked by identical rectangular sections, won the competition.3 Construction on the foundation of the U.S. Capitol Building began on Jenkins Hill—what we know today as Capitol Hill— in August 1793 and the cornerstone of the building was laid in a public ceremony that September.4 Click here to learn more about the enslaved households of President George Washington and President Thomas Jefferson.

Architectural drawing of William Thornton's design for the U.S. Capitol

Library of CongressThe lengthy process of constructing the U.S. Capitol relied upon free and enslaved laborers at every step. As a city in its infancy, Washington, D.C. frequently experienced a shortage of free, white craftsmen for hire on construction projects.5 Instead, enslaved laborers from the surrounding slave states of Maryland and Virginia made up a bountiful, cheap workforce that could be “hired out” for work on the President’s House and the Capitol.6 To read more about the construction of the White House, click here. The Commissioners of the Federal District paid regional plantation owners for use of their enslaved workforce; the owners pocketed the wages, while the commissioners provided housing, some medical care, and rations for all laborers under their watch.7 It was financially lucrative for both parties, keeping labor costs down for the fledgling government while providing “between $55 and $65 a year” for slave owners.8 It also prevented the federal government from purchasing and owning enslaved individuals outright. Polish writer Julian Niemcewicz observed the Capitol worksite while visiting Washington, D.C. in the 1790s, writing:

I have seen [slaves] in large numbers and I was very glad that these poor unfortunates earned eight to ten dollars per week. My joy was not long lived: I am told that they were not working for themselves; their masters hire them out and retain all the money for themselves. What humanity! What a country of liberty.9

Enslaved laborers toiled alongside free Black and white men in the Federal City, and many worked on both the White House and the U.S. Capitol. Research by historian Bob Arnebeck shows that at least 200 known enslaved laborers were a part of these projects – click here to view an index of these individuals.10

This map, created by historian Lina Mann, shows the movement of enslaved laborers sent from Maryland and Virginia to Washington, D.C. to work on the U.S. Capitol and White House construction projects. Some locations are exact, while others are estimates based on genealogical research, census data, and other primary source materials.

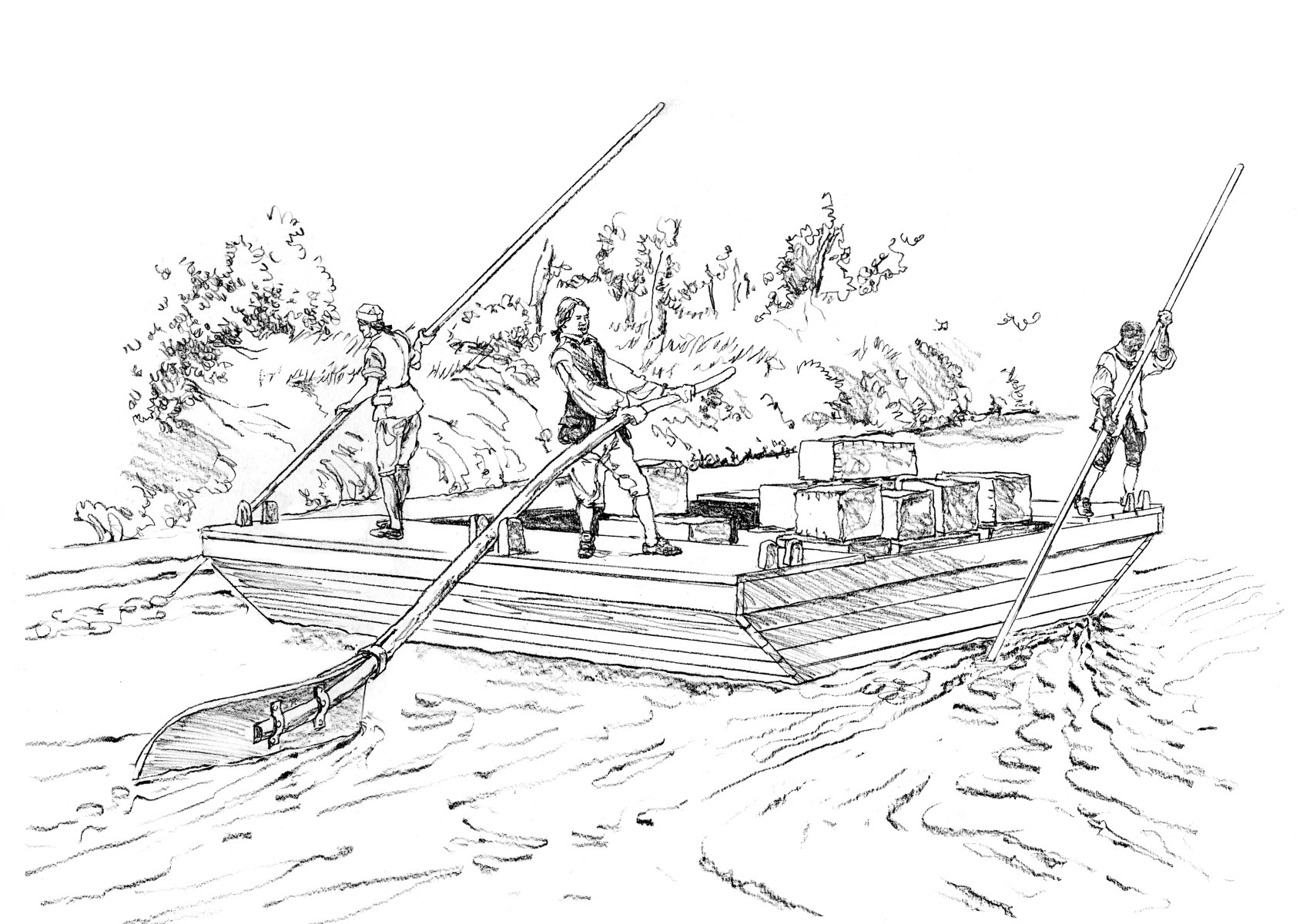

The Capitol construction process began with the excavation of raw materials. One of these resources was Aquia sandstone, applied to the exterior façade and interior details of the Capitol Building.11 Much of the sandstone came from quarries in Stafford County, Virginia—in particular Government Island, which was purchased by the U.S. government in 1791.12 According to historian William C. Allen, the quarry itself was staffed by “forty ‘stout armed’ Negro men” and a number of free workers, and the labor executed there was physically intense.13 These men excavated stone from the earth and transported it via boat up the Potomac River to Washington, D.C. for use in building projects.

When construction began, Capitol Hill was wooded. Laborers thus worked to clear the area by chopping trees, moving soil, and preparing for the building’s foundation.14 Once they had cleared the area, enslaved laborers worked in a number of capacities onsite, including “carpentry, masonry, carting, rafting, roofing, plastering, glazing, and painting” as well as brickmaking and sawing.15 Their work required skill, practice, and endurance, though enslaved workers typically worked without compensation or recognition.16

This drawing by Dahl Taylor is of three workers delivering stone from the quarry to the building site by ferrying it up the Potomac River and into Tiber Creek. It is one in a series of eleven drawings illustrating the journey of the stones used to build the White House from Aquia Quarry to the building site.

White House Historical AssociationOverseers supervised the progress of enslaved workers each day. D.C.’s commissioners directed them to “keep the yearly hirelings at work from sunrise to sunset particularly the negroes” and workhands typically labored six days a week.17 Exhausted at the end of a long day of physical toil in the hot, humidity of summer or the cold of D.C. winters, enslaved men retired to “huts” onsite.18 Overseers distributed meal rations including whiskey, Indian or cornmeal, and salted meats.19 After a night of rest, their work cycle began again.

Capitol construction took a physical and emotional toll on these individuals. Workers participated in backbreaking physical labor while exposed to the elements six days a week. Dysentery, smallpox, and malaria plagued Washington, D.C. in the 1790s and illness, injuries, and fatigue accompanied the intense physical labor undertaken onsite.20 To ensure a healthy—and therefore useful—workforce, commissioners provided basic medical care for injured or ill workers.21 Some enslaved laborers were even inoculated against smallpox to guarantee productivity; both the price of inoculation and recuperation were deducted from their owner’s pay.22 Moreover, most of these enslaved workers came from plantations in southern Maryland or northern Virginia, and were separated from friends and family upon being sent to work in the Federal City.

These undesirable conditions resulted in various documented forms of resistance, including self-emancipation from work on federal building projects. In 1793, for example, an enslaved laborer named Jacob “absconded from his employment in the Federal City,” according to Bob Arnebeck.23 His owner offered a $6 reward for his return. In 1827, Christina Hamilton placed an ad for a runaway named Daniel Brown in the National Intelligencer which reads: “Ran away from the subscriber, on Sunday…a Negro Man…who calls himself Daniel Brown… he was purchased about a year ago… and has been employed of late as a laborer at the Capitol.”24 Hamilton offered a $50 reward for his return. Everyday resistance by enslaved workers also may have taken the form of deliberately slow labor—a reclamation of their own time and energy.25

National Intelligencer ad for Daniel Brown, an enslaved laborer at the Capitol who self-emancipated in November 1827.

Library of CongressIndeed, the construction process of the Capitol was excruciatingly slow and continued from the 1790s through the 1860s, delayed by inadequate funding and labor shortages. Though the first meeting of Congress occurred onsite in 1800, the building itself was not complete, and progress was later exacerbated by the burning of Washington, D.C. by British troops in August 1814. Enslaved labor contributed to the reconstruction of the Capitol and “huts” and provisions were once again instituted on Capitol Hill.26 On a visit to Washington, D.C. the following year, abolitionist author Jesse Torrey stood at “the old capitol (then in a state of ruins from the conflagration by the British army)” and lamented: “it is a fact that slaves are employed in rebuilding this sanctuary of liberty.”27 Frequent expansions to the building throughout the nineteenth century, including the addition of the Capitol Dome, made room for America’s growing legislature.28 Enslaved labor continued to augment a number of new projects—perhaps most notably, the Statue of Freedom atop the U.S. Capitol Dome, owed in part to the labor and skill of enslaved artisan Philip Reed. To read more about Philip Reed, click here.

Capitol construction, 1859. Enslaved labor augmented many nineteenth-century construction projects, including the addition of the Capitol Dome.

Library of CongressThe building was also a silent witness to the atrocities of slavery in the nation’s capital. Nearby stood the Yellow House slave jail, where future President Abraham Lincoln commented in 1854 that “in view from the windows of the capitol” he could see “a sort of negro-livery stable, where droves of negroes were collected, temporarily kept, and finally taken to Southern markets, precisely like droves of horses…”29 To learn more about the Yellow House jail, click here. Abolitionists often juxtaposed the Capitol, the symbolic heart of American democracy and liberty, with the hypocrisy of slavery, writing: “Scenes have taken place in Washington this summer that would make the devil blush through the darkness of the pit, if he had been caught in them. SIXTY HUMAN BEINGS, were carried right by the Capitol yard to the slave ship!”30

"A Slave-Coffle passing the Capitol" c. 1815. Many abolitionists used imagery such as this to emphasize the hypocrisy of slavery in the nation's capital and America writ large.

Library of CongressIn 1862, slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia and by 1868, major expansions and additions to the Capitol were complete. The U.S. Capitol Building as we know it today would not stand without the contributions of hundreds of enslaved and free laborers. Today, these individuals are recognized by a commemorative marker in Emancipation Hall, added to the Capitol Visitor Center in 2012—over two hundred years after the Capitol’s initial construction. It features a block of a Aquia Creek sandstone and a plaque that reads: “This sandstone was originally part of the United States Capitol’s East Front, constructed in 1824-1826. It was quarried by laborers including enslaved African Americans and commemorates their important role in building the Capitol.”31 This acknowledgement, albeit long overdue, helps share the full story of the enslaved and free laborers that built our nation’s capital with millions of visitors each year.

This marker was added to the Capitol Visitor Center in 2012 to commemorate the enslaved and free laborers who built the U.S. Capitol.

Architect of the CapitolMany thanks to Dr. Felicia Bell, Director of Public Engagement at the Smithsonian's “Our Shared Future: Reckoning with Our Racial Past” Initiative for her assistance and expertise.

James Buchanan is often regarded as one of the worst presidents in United States history.1 Many historians contend that Buchanan’s...

On February 11, 1829, members of Congress convened to certify votes for President and Vice President of the United States as Andrew...

In 1821-1822, Susan Decatur requested the construction of a service wing. The first floor featured a large kitchen, dining room,...

Built in 1818-1819, Decatur House was designed by the English architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe for Commodore Stephen Decatur and Susan...

Through research and analysis of written accounts, letters, newspapers, memoirs, census records, architecture, and oral histories, historians, museum professionals, and...

Without photographs, paintings, or other visual representations of the Decatur House Slave Quarters from the antebellum period, it is difficult...

President William Henry Harrison’s famously brief month-long tenure at the White House makes it difficult to research the inner wo...

Upon stepping into the White House China Room, visitors encounter tableware from nearly every presidential administration or first family. Tucked...

On May 2, 1812, Captain Paul Cuffe arrived at the White House for a meeting with President James Madison.1 The internationally renowned...

The First Baptist Church of the City of Washington D.C. was founded in 1802, shortly after Washington D.C. became...

“Would it be superstitious to presume, that the Sovereign Father of all nations, permitted the perpetration of this apparently execrable tr...

At the corner of H Street and Connecticut Avenue, the United States Chamber of Commerce Building sits where a three-and-a-half...